Texas 2025: A Sudden and Shattering Flood

This past Fourth of July, while many celebrated across the nation, tragedy struck the Texas Hill Country. A quiet holiday morning shifted in minutes as relentless storms sent walls of water racing through river valleys. Videos showed roads vanishing under churning runoff, homes collapsing into fast-moving currents, and families shouting for help as the flood swallowed everything in its path. The devastation came fast and left entire communities stunned.

Warm, humid air from the Gulf of Mexico kept feeding into central Texas. A slow-moving disturbance overhead caused powerful thunderstorms to re-form over the same corridors again and again. Meteorologists call this pattern “training.” Storms march across one strip of land like boxcars on a track, dropping several inches of rain in just a few hours.

That setup is especially dangerous in the Hill Country, a maze of steep limestone hills, narrow canyons, and dry creek beds. Thin, rocky soils cannot soak up water quickly, so intense rain races downslope almost immediately. Small creeks that are often little more than trickles exploded into roaring brown rivers, funneled into the Llano, Pedernales, and Guadalupe systems. As water surged out of the canyons, those places were hit with almost no warning. Roads vanished under feet of water, and entire communities were cut off until rescue crews could reach them.

The loss of life—especially so many children—was heartbreaking. Families and neighbors now carry deep scars. Their grief forces us once again to confront nature’s power and the lasting vulnerability of the places we build and call home.

Flash Floods in American Memory

Flash floods have shaped American history for generations. Each one reminds us that we cannot stop extreme rain, but we can reduce its impact. After every major event, local agencies, scientists, and communities work together to understand what happened and strengthen defenses. Aerial imagery has become one of the most important tools in that process. It helps experts see damage patterns, guide rescue efforts, and plan long-term mitigation.

Within days of the 2025 Texas flood, NOAA aircraft flew over the hardest-hit areas and captured high‑resolution photographs. These images guided recovery teams and offered early insights into how the flood moved across the landscape. This approach reflects a long tradition. Long before drones and digital sensors, aerial photographs documented earlier disasters and taught planners essential lessons.

By comparing post-flood imagery with historical aerial photographs, analysts can identify channel migration and floodplain expansion. They can also spot infrastructure vulnerabilities and development patterns that increase risk over time.

For planners, environmental consultants, developers, and researchers, floods like these are not just historical events—they are case studies. Understanding where water moved, where infrastructure failed, and how landscapes changed is critical for floodplain mapping, environmental due diligence, and long-term land-use decisions. Historic aerial imagery provides a rare, visual record that allows those patterns to be studied decades later.

One of the first major U.S. floods to be captured from above was the Great Southern California Deluge of 1938.

The 1938 Flood: Aerial Evidence of a Regional Disaster

In late February and early March 1938, a pair of intense Pacific storms parked over Southern California and dropped almost a full year’s worth of rain in just a few days. The result was one of the worst floods in the recorded history of Los Angeles, Riverside, and San Bernardino Counties. Between 113 and 115 people died. More than 5,600 buildings were destroyed, and another 1,500 were damaged. Large parts of the Inland Empire and coastal plain disappeared under water.

The storms focused on the high San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains, where some peaks recorded more than 32 inches of rain. Steep, short mountain watersheds funneled that water into every major river system at once. The Los Angeles, San Gabriel, Santa Ana, and Mojave Rivers all burst their banks. Torrents of water and debris poured out of the canyons and across farms, rail lines, and new suburbs. Civic leaders later described the disaster as roughly a “50‑year flood” — rare, but devastating enough to force a complete re‑thinking of how the region handled its rivers.

Los Angeles County: A City Brought to a Standstill

In Los Angeles County the flood was less about dramatic aerial scenes and more about everyday life breaking down. Roughly 108,000 acres went underwater. New subdivisions in the San Fernando Valley, many built on old riverbeds and washes, were suddenly swamped or washed out. Dozens of bridges failed, cutting highways and railroads and briefly isolating the region from the rest of the country.

Neighborhood streets turned into canals deep enough for rowboats and motorboats. Downtown basements and utility tunnels filled with water, knocking out telephone, telegraph, and power in key districts. By the time the waters receded, thousands of Angelenos were homeless and whole neighborhoods were left buried in mud. The experience pushed city leaders to finally line the Los Angeles River and its tributaries in concrete. This decision permanently reshaped how the city looks and lives with water.

Inland Empire Underwater

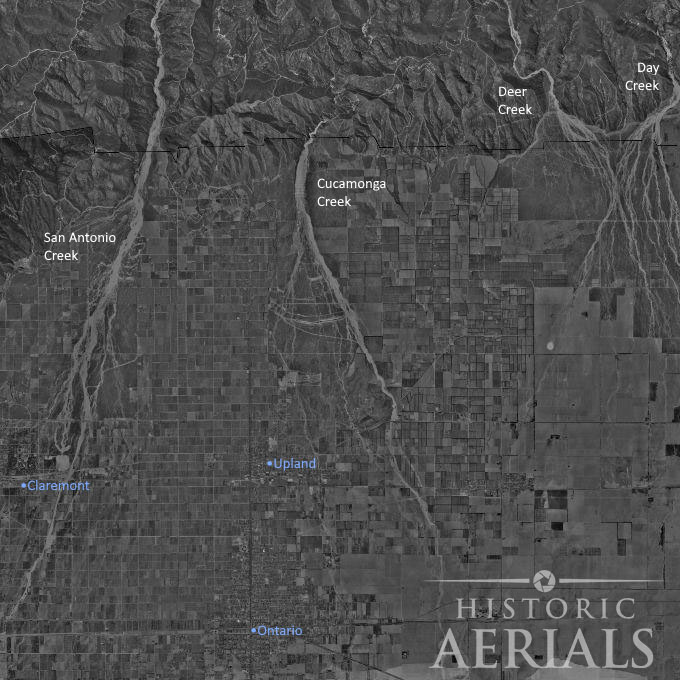

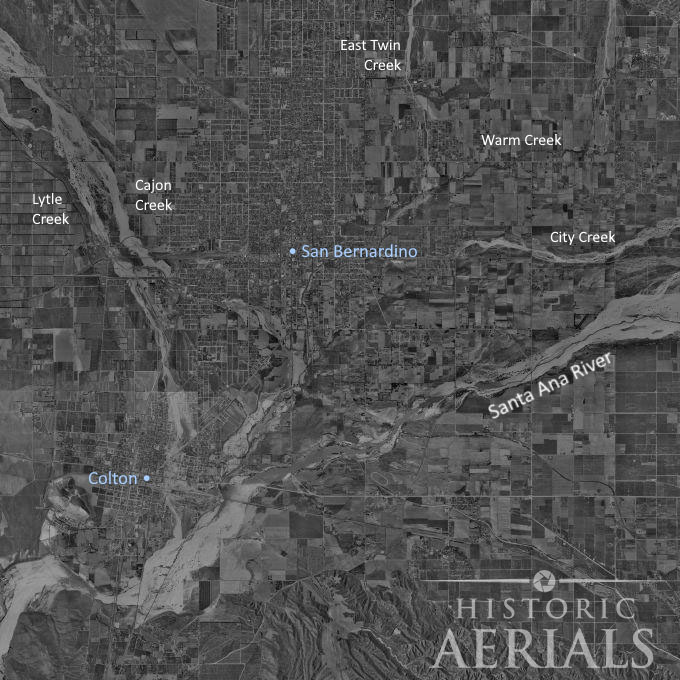

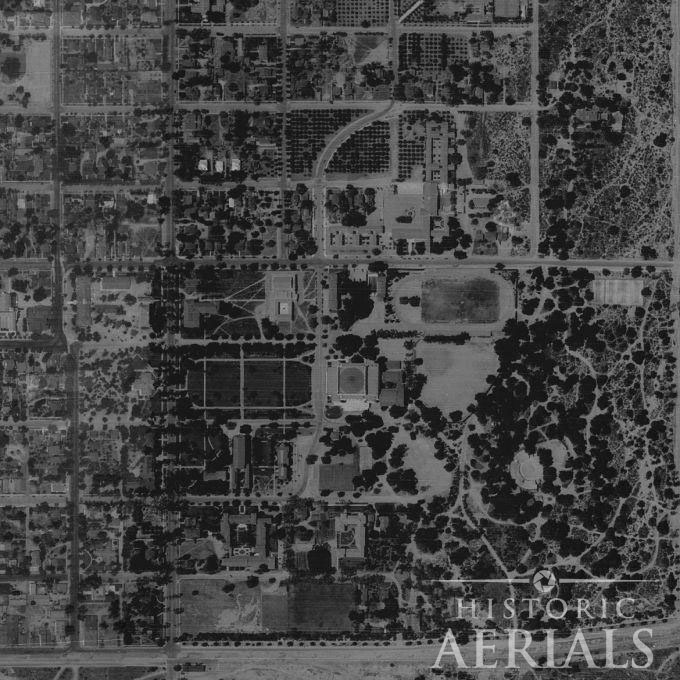

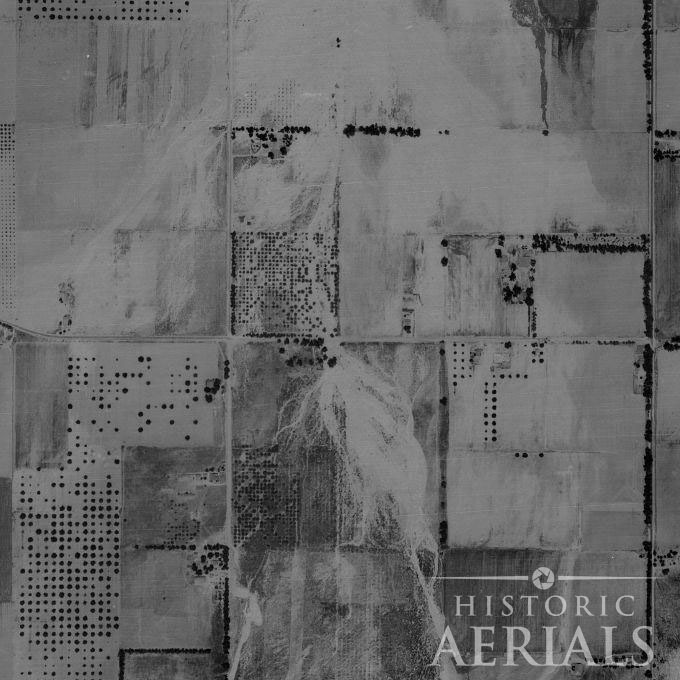

East of Los Angeles, the Inland Empire became the focus of much of the surviving aerial imagery.

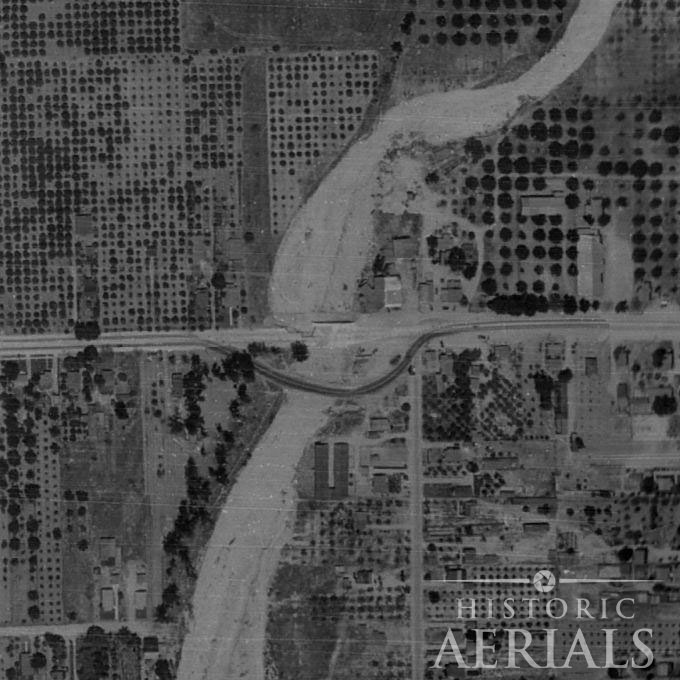

HistoricAerials preserves striking views from the 1938 flood, especially in the belt between Pomona and San Bernardino. From above, farm country and suburbs are almost unrecognizable: huge brown sheets of water erase property lines. Roads simply end at ragged shorelines. Isolated clusters of homes sit on tiny islands of high ground.

On the ground, San Bernardino itself “turned into an island.” Water filled streets, businesses, orchards, and low‑lying neighborhoods. Residents used rowboats to move through residential blocks. In Ontario and Upland, major streets like Euclid Avenue became fast‑moving streams, and entire neighborhoods were cut off for days.

Rivers and Creeks Turn Violent

Much of the destruction came from the Santa Ana River, fed by runoff and snowmelt from the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains. At the flood’s peak, the Santa Ana’s flow was estimated around 100,000 cubic feet per second — an almost Mississippi‑like volume that overwhelmed levees and spilled far beyond the mapped channel. In places, the river spread nearly four miles wide and several feet deep, turning orange groves and dairies into a shallow inland sea that lingered for weeks.

Historic communities along the river paid a heavy price. The town of Agua Mansa—once the largest settlement between Los Angeles and New Mexico—was effectively wiped off the map. When a levee failed near the mouth of Santa Ana Canyon, an eight‑foot wall of water tore through western Riverside County and into Orange County, smashing railroad bridges and sweeping houses into the groves.

Smaller creeks turned deadly as well. Lytle Creek and Cajon Creek became raging rivers that ripped out sections of Route 66 and damaged railroad lines through Cajon Pass. In the Mojave Desert, the Mojave River surged to an estimated 70,600 cubic feet per second near Victorville. The flood washed out ranches, bridges, and long stretches of the AT&SF railroad. For nearly three weeks, rail service to Arizona and Nevada was cut.

The aerial photographs from 1938 capture the aftermath of this event: bridges snapped in two, tracks dangling over eroded embankments, and whole segments of river that appear to have shifted course overnight.

Building Flood Control After 1938

Before 1938, Southern California mostly relied on small levees and simple earthen channels. The flood exposed just how fragile that system was. In the years that followed, local governments and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers launched a regional campaign to contain the next “1938‑scale” storm.

Major projects included:

- Prado Dam (completed 1941) at the mouth of the Santa Ana River, to hold back mountain runoff before it could spread across the Inland Empire.

- San Antonio Dam in the Cucamonga foothills, to protect Upland, Cucamonga, and neighboring communities.

- Concrete river channels throughout Los Angeles, the San Gabriel Valley, and the Inland Empire, designed to move floodwater quickly to the ocean before it could spread into neighborhoods.

What Historic Aerial Imagery Reveals About Flood Risk

Today, the historic images from 1938 highlight both the scale of destruction and the determination to rebuild safer communities. They underscore how vulnerable low‑lying areas can be and how vital strong flood‑control systems are.

Tools like historic aerial imagery allow researchers, planners, and property professionals to explore these changes firsthand—comparing past floods with present landscapes to better understand risk before the next storm arrives.

As climate change accelerates, these lessons grow even more urgent. Warmer air holds more moisture, which fuels intense downpours and more sudden flash floods. Our best protection comes from a clear understanding of risk and a commitment to stronger defenses—modernized dams, restored natural waterways, smarter zoning, and real‑time flood‑monitoring technology.

Historic aerial imagery and modern science give us the tools to compare past and present, measure progress, and plan wisely. The floods of 1938—and the tragedy in Texas in 2025—share a message we cannot afford to ignore: we may never control the rain, but with foresight and collective action, we can protect our communities and build a safer, more resilient future.