I’ve lived in the Houston area most of my life. But I knew nothing about Dean Corll—nicknamed the “Candy Man.” The story hit harder when I dug in. Corll was a serial killer who abducted, tortured, and brutally murdered at least 28 teenage boys and young men in the Houston between 1970 and 1973.

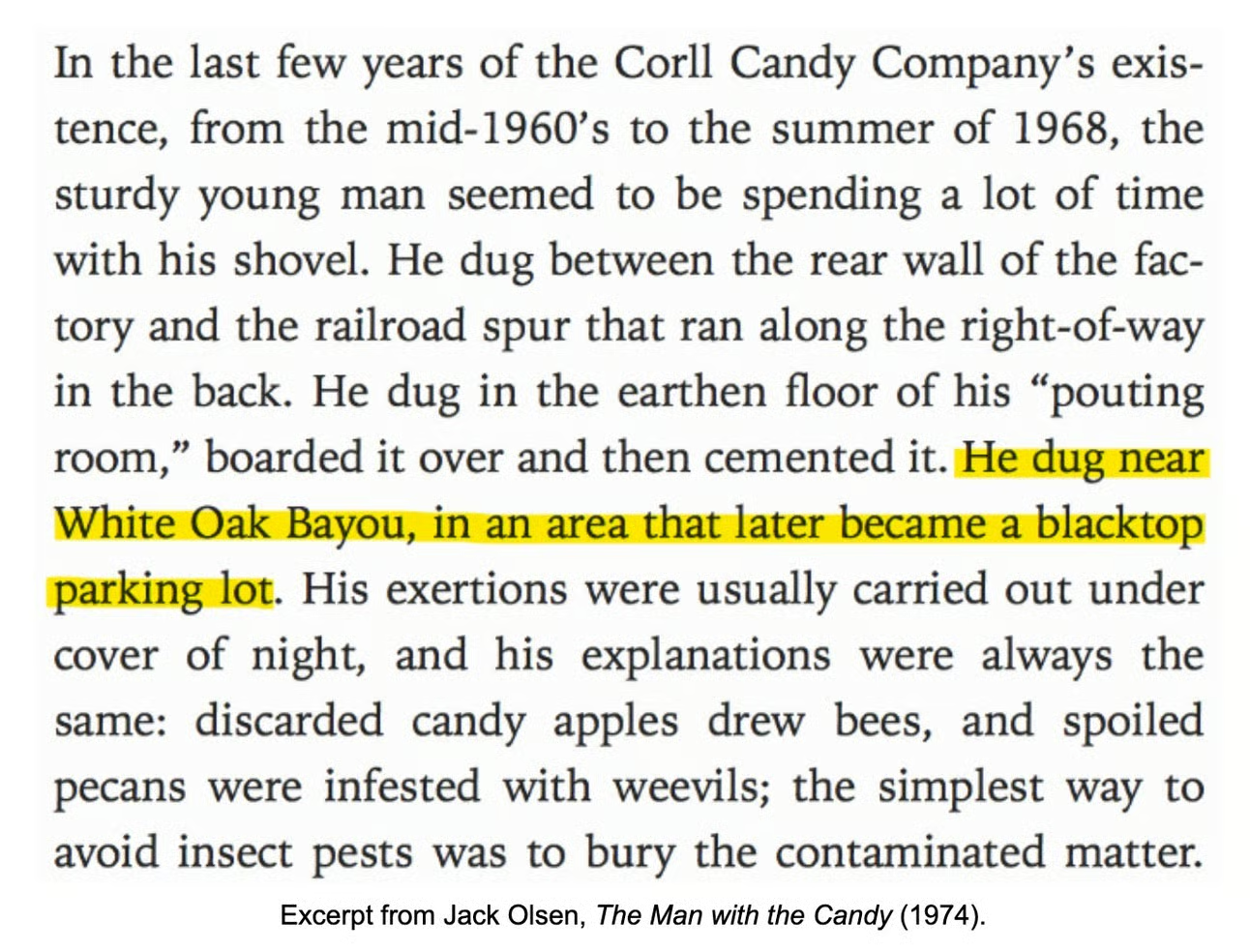

I picked up the book The Man with the Candy by Jack Olsen. As I read through the story, I began researching the locations mentioned in the book—the places where Corll and his accomplices had killed and buried his victims. That’s when I came across something chilling.

Mapping Clues from Aerial Views

I came across a Reddit post where someone was investigating one of the claims in Olsen’s book. The post featured aerial images from HistoricAerials.com showing a location where one of Corll’s victims might still be buried.

“…Olsen mentions Dean Corll doing some digging near White Oak Bayou during his time with the Corll Candy Company, in an area that later became a blacktop parking lot…”

“The [book] was written in 1974, so we know the area was paved over before then. We also know the area was yet to be paved while Dean worked at the Corll Candy Company, which closed in 1968.”

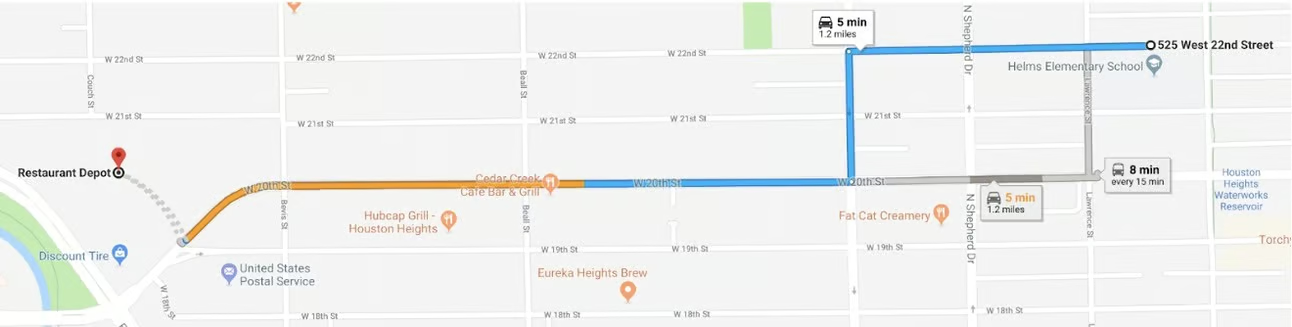

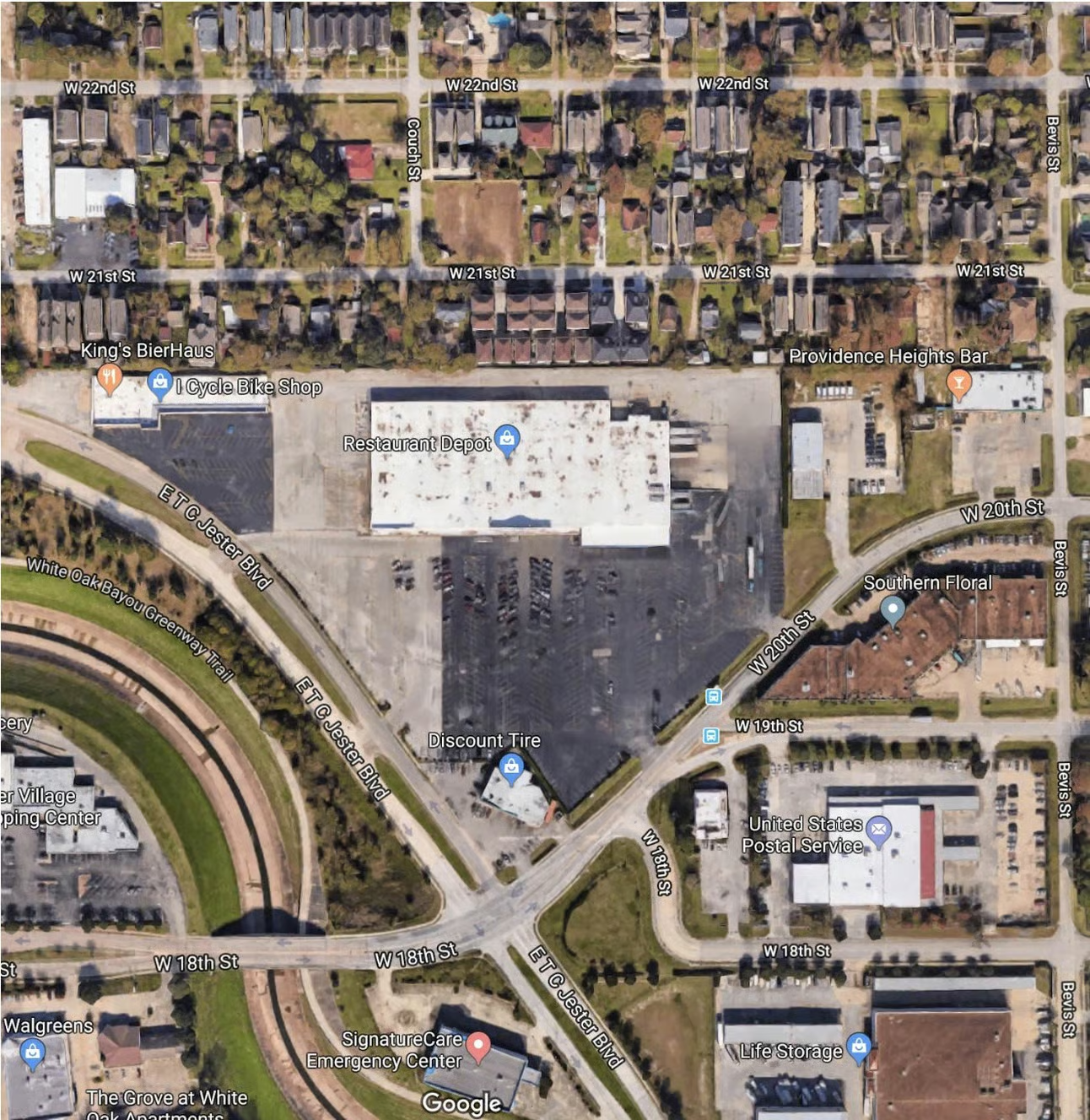

Looking on historicaerials.com, I found a location next to White Oak Bayou that was an open field in 1966 and a paved lot in 1973. It is 1.2 miles due west of the site of the old Corll Candy Company.

“An oft-repeated narrative of the Dean Corll case is that the Houston PD simply quit searching for bodies once the count surpassed that of Juan Corona’s 25 murders. They abruptly shut down the investigation, favoring damage control over locating possible additional victims.

“If this parking lot is the location spoken of in The Man with the Candy, then it seems like a good place to investigate with ground penetrating radar. If something was down there in 1973, it’s still there now.”

Field Becomes Parking Lot

That shift—field → parking lot—might seem mundane. But consider this: if Corll used the site for covert activity, the visible change tells a story. The features of the land changed, but the traces of what went on beneath may still exist. If the ground was disturbed before paving, it may hold clues. If bodies were buried, the layering of time might have preserved evidence.

And yes—on Google Maps in 2018 the lot looks essentially the same as it did in the 1973 aerial. That opens a provocative question: could ground-penetrating radar today still find something tied to the earlier narrative?

Technology Meets Memory

What we’re witnessing here is a convergence of history, geography and investigation. HistoricAerials offers the researcher—amateur or professional—a chance to rewind the land and observe human activity from above. We often think of cold-case work as dusty files and worn photos. But the sky holds one more vantage.

In the case of Dean Corll, the brutal facts are well documented—but the terrain where parts of the crime played out remains less examined. By revisiting changes in land use, and by cross-referencing witness accounts, book details and aerial timelines—1966, 1973, 2018—we open doors to new questions.

Why This Matters

Because the story didn’t end in 1973. Investigators still call it one of the worst serial-murder sprees in U.S. history. The possibility remains: unknown victims, altered terrain, forgotten evidence.

And because for every person who says “that’s history,” there are families still waiting. Even a small lead can shift the scale toward closure. Tools like HistoricAerials don’t replace boots on the ground, police reports or forensic labs—but they add one more layer.

Your Neighborhood Holds Stories Too

If a parking lot might hide more than meets the eye, so could your own backyard. The open field turned asphalt. The factory wing that went quiet. The bayou path re-charted. The aerial record is a silent witness. The vantage from above alters the narrative. The land remembers, even when we’d rather forget.