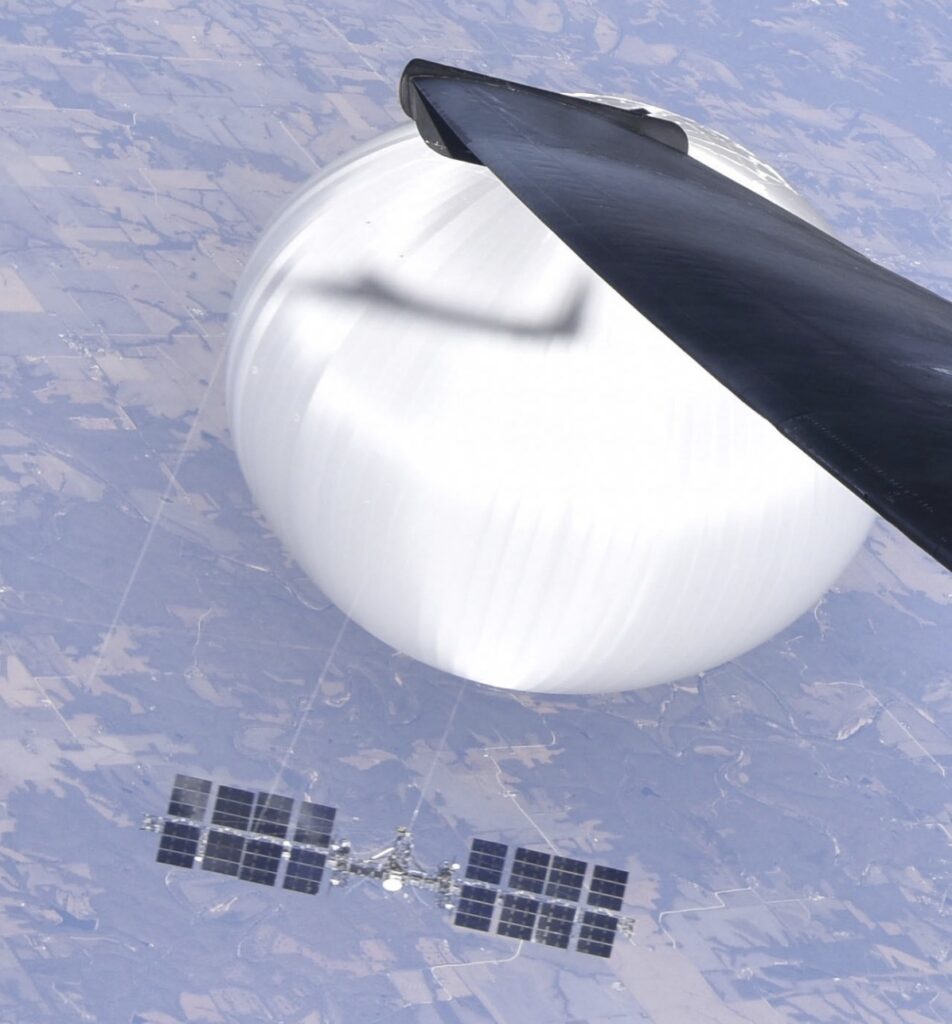

In early 2023, a high-altitude Chinese surveillance balloon drifted into U.S. airspace, prompting a diplomatic crisis and its eventual shootdown. The revelation that similar balloons had conducted missions over at least 40 countries was a stark reminder that aerial reconnaissance is nothing new. Long before satellites and spy planes, armies looked to the sky—beginning with balloons.

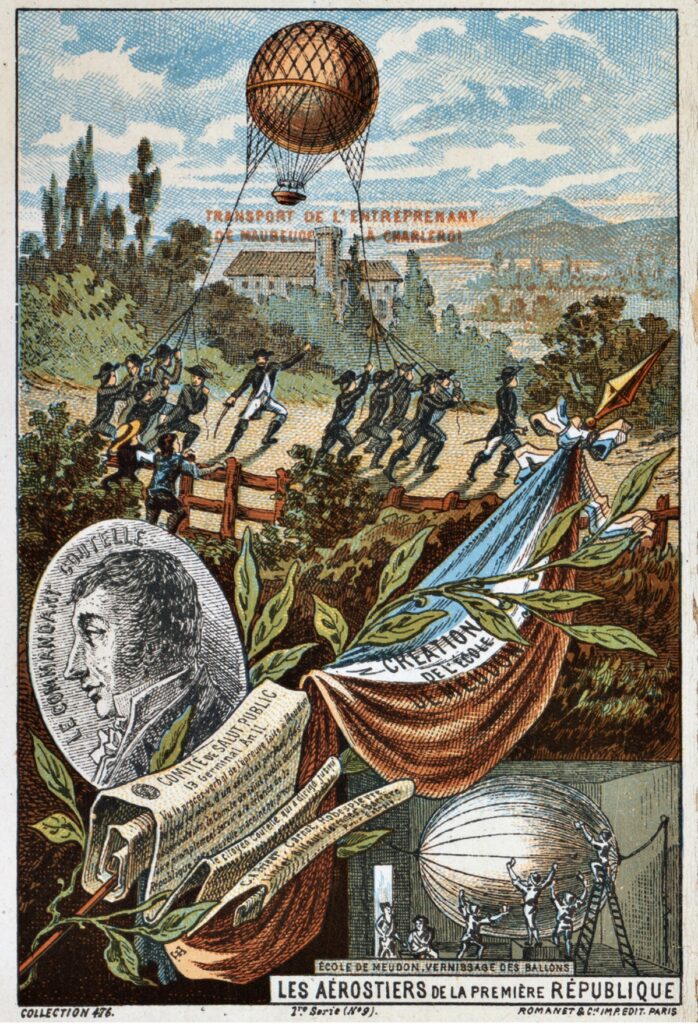

The idea of military ballooning emerged soon after the Montgolfier brothers’ first successful flight in 1783. The potential for aerial observation quickly captured the imagination of military strategists, and during the French Revolutionary Wars, France became the first nation to deploy balloons in battle.

At the Battle of Fleurus in 1794, the French Army used L’Entreprenant, a tethered balloon, to monitor enemy movements from above. Suspended high in the sky, aeronauts provided real-time reconnaissance, marking the dawn of aerial warfare. This intelligence contributed to a French victory, leading to the formation of the world’s first military balloon unit, the Compagnie d’Aérostiers.

However, by 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte, unconvinced of ballooning’s practicality for fast-moving campaigns, disbanded the unit. Military ballooning faded into obscurity—at least for a time.

Resurgence in the American Civil War

More than half a century later, war broke out in the United States, and military ballooning re-emerged as a valuable tool. The vast battlefields of the Civil War presented an opportunity for aerial observation to provide much-needed intelligence.

The most prominent figure in this revival was Thaddeus Lowe, an experienced aeronaut who captured President Lincoln’s attention with a dramatic demonstration. In June 1861, Lowe ascended in a hydrogen balloon over Washington, D.C., and used a telegraph to send a message from midair. Convinced of its potential, Lincoln approved the creation of the Union Army Balloon Corps, with Lowe at its head.

From 1861 to 1863, Lowe’s balloons ascended over battlefields, offering Union commanders a critical advantage. They provided intelligence on Confederate movements, and Lowe even developed portable hydrogen generators, allowing balloons to be deployed in remote areas.

Lowe, however, was not alone in his efforts. John LaMountain, another aeronaut, had already been experimenting with balloon reconnaissance over Confederate positions near Fortress Monroe. Though working independently, his early flights helped prove the concept. Later in the war, James Allen took over operations, ensuring the continuation of aerial observation until logistical challenges led to the Corps’ dissolution in 1863.

Despite its short lifespan, the Balloon Corps demonstrated that aerial reconnaissance could influence military strategy—a concept that would shape future warfare.

Although military ballooning faded once again, it did not disappear. In the years following the Civil War, aeronauts sought new opportunities to apply their craft. Among them were John and Ezra Allen, who took their expertise to South America, where political upheaval and military conflicts created a demand for aerial intelligence.

In Part II, we’ll explore how the Allen brothers introduced balloon reconnaissance to a new frontier, carrying on the legacy of aerial warfare in ways few remember today.