High above the mud and trenches of World War I, tethered balloons swayed with the wind, carrying observers who scanned the horizon for any sign of enemy movement. These hydrogen-filled “sausages” were far more than curiosities – they were critical eyes in the sky.

Europe during the Great War was the pinnacle of military ballooning, as all major armies on the European front deployed observation balloons to gather intelligence and direct their artillery. From the static trench warfare in France and Flanders to the mountainous Italian front, balloons became ubiquitous on the battlefield.

In this final installment of Balloons of War, we explore the technology behind WWI ballooning, the vital roles these balloons played in combat, their use in early aerial photography, and their peaceful retirement from military conflicts to leisurely recreation.

(Because this era coincided with vastly improved camera technology, it produced a wealth of incredible images. As a result, you’ll find more photographs in this article than in previous installments. The writer begs your indulgence.)

Eyes in the Sky

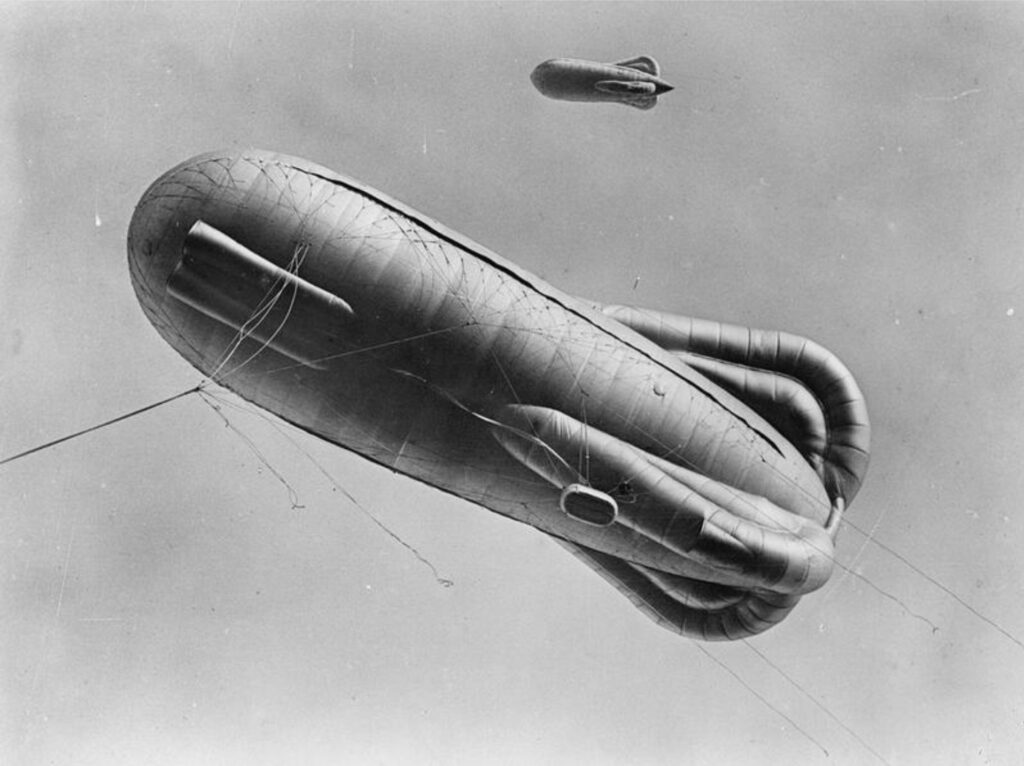

At the outset of WWI, the spherical balloons of the previous century quickly evolved into more advanced “kite balloons.” These were elongated, aerodynamic hydrogen balloons that were designed to remain stable in wind and provide a steady platform for observers. Germany had pioneered the Parseval-Sigsfeld Drachen (“dragon”) balloon, a cylindrical or sausage-shaped design with tail stabilizers to keep it steady.

The Allies responded with the French-designed Caquot balloon in 1916, featuring three large tail fins for even greater stability. The Caquot type proved completely superior in high winds, enabling ascents to higher altitudes than previously possible.

A balloon’s routine involved ascending at dawn, and remaining aloft for hours observing the enemy. Balloons often signaled the opening of major offensives. Whenever a soldier in the trenches used the phrase “the balloon’s going up,” it meant something big was about to happen.

Australian soldiers watch an observation balloon ascend over the ruins of Ypres, Belgium. 1917. Source: Australian War Memorial

Observation balloons were tethered by a steel cable attached to a powered winch truck. This allowed crews to raise or lower the balloon as needed and haul it down quickly if enemy aircraft appeared. The winch system (often mounted on a truck) also gave a degree of mobility – a balloon unit could deflate and pack up its balloon to move forward as the front lines shifted.

Communication is Key

Unlike the newly invented airplanes, balloons had the advantage of a direct communication line to the ground. Observers communicated via telephone wires running along the tether cable. Real-time communication made the difference. Suspended in wicker baskets tethered hundreds of feet above the trenches, balloon observers scanned enemy positions with binoculars and telephoned coordinates back to artillery units.

A pilot in a fast-moving airplane might only drop a message or take a photograph to be developed later. But balloon observer could observe continuously, direct gunfire with pinpoint accuracy, observe troop movements, and detect incoming offensives well before ground-based observers could.

The “Balloon Busters”

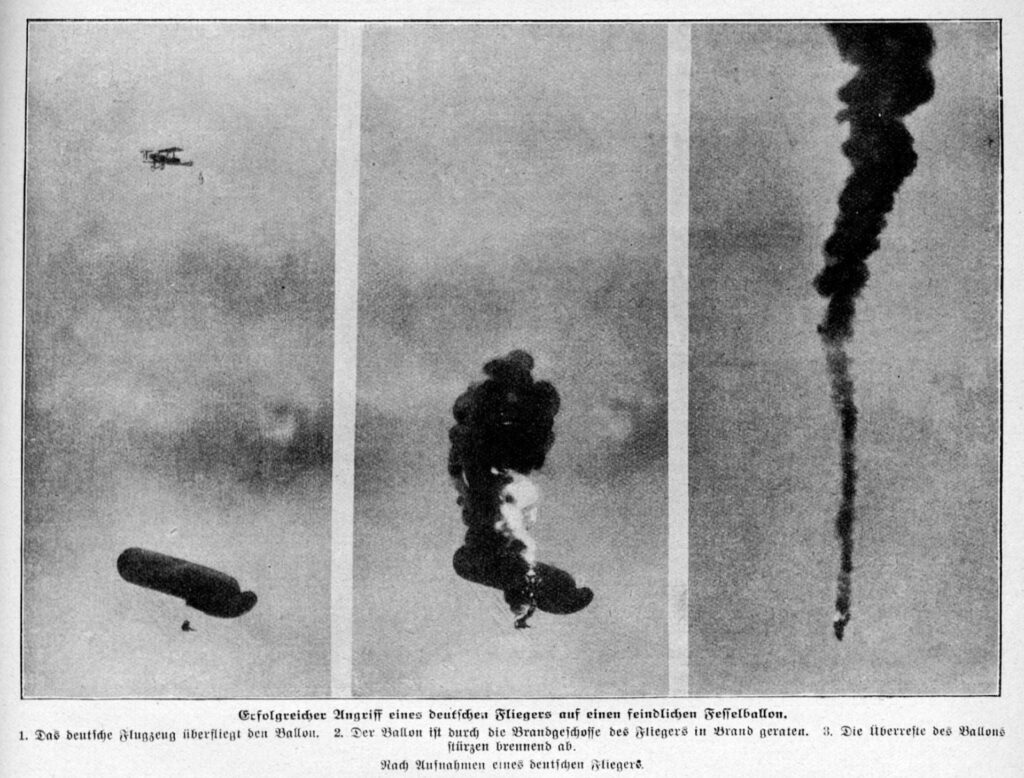

To counter this advantage, nations developed specialized tactics and aircraft units for “balloon busting.” The hydrogen gas also made balloons literally explosive targets, sometimes erupting in a fireball that could take down an overly aggressive plane. These missions were exceptionally dangerous – balloons were usually heavily defended, and attacking pilots dived into a gauntlet of anti-aircraft fire.

One of the most daring “balloon busters” of World War I was Phoenix native Lt. Frank Luke Jr., a U.S. Army Air Service pilot whose short but ferocious combat career earned him legendary status. In just 17 days during September 1918, Luke destroyed 14 German observation balloons and four enemy aircraft, often engaging in reckless solo missions at dawn or dusk when balloons were silhouetted and most vulnerable. Luke’s final sortie ended in tragedy – after being wounded and forced to land behind enemy lines, he reportedly died in a gunfight with German soldiers.

For all their tactical importance, balloons were sitting ducks, and their flaming deaths were dramatic reminders that the skies were becoming deadlier and more crowded. The contest between slow-moving balloons and fast fighter planes became an intriguing subplot of the war in the air, especially in 1917–1918. But even as brave crews and new tactics kept the balloons flying, technological progress was about to overtake them.

Photographing the Front

By WWI, aircraft were increasingly used to photograph enemy trenches, but balloon observers also carried cameras aloft to capture detailed images of the front. Their stationary position had an advantage: a balloon could linger over a sector and take multiple photos from the same angle, useful for stereo imaging and mapping.

From their lofty vantage point, observers could detect changes in enemy defenses – for example, new trenches being dug or preparations for an attack – which might be missed by ground scouts. These balloon photos, often taken in sequence along the front, enabled analysts to track the progress of bombardments (by comparing before-and-after images of fortifications) and to locate targets that aircraft reconnaissance missions could later examine more closely.

The Last Battlefront for Balloons

By war’s end, balloons were still being deployed, but their role was diminishing. Fixed-wing aircraft, now capable of both reconnaissance and combat, could fly farther, faster, and with greater versatility. Balloons were relegated to static defense zones and artillery spotting. Their final contribution was both symbolic and practical—a nod to the old world in a new kind of war.

The end of World War I effectively closed the chapter on balloons as frontline military tools. Though used sporadically in World War II for barrage defense against low-flying aircraft, and for the short-lived Japanese balloon bomb offensive, the days of balloons as battlefield eyes were over.

From War to Wonder

And yet, the story of hot air balloons didn’t end in the mud of Flanders or the shattered forests of the Argonne. With the cessation of hostilities came a shift in the skies. No longer instruments of war, balloons were reborn as vessels of leisure, science, and spectacle.

Throughout the 20th century, ballooning grew into a peaceful pastime. Festivals from Albuquerque to Cappadocia fill the skies with bursts of color, drawing crowds to watch them drift silently overhead. The same awe that once struck generals now inspires photographers and families. High above the noise and haste, balloons continue to offer something the battlefield never could—tranquility, perspective, and wonder. What was once an instrument of conflict now carries birthday wishes, marriage proposals, and scientific instruments into the stratosphere.

Hot air balloons had a long and varied history in military applications worldwide before World War I began in 1914. From the observation posts of the American Civil War to the highland skies of South America, the parched battlefields of Africa, and finally the entrenched fronts of Europe, these lighter-than-air vessels offered a bird’s-eye view of the battlefield long before powered flight took over. The Great War marked the final fling for balloons in battle—drifting silently above the chaos, tethered to a fading past as modern warfare surged ahead.