In 1925, Edith Keating was hired to type memos at Fairchild Aerial Surveys in New York City. It was a standard administrative role, but Keating proved to be a distracted stenographer. Instead of focusing on her typewriter, she spent her time studying the aerial photographs pinned to the office walls. Within months, she traded her desk for the open cockpit of a biplane, eventually becoming aerial photography’s first woman to be hired full time.

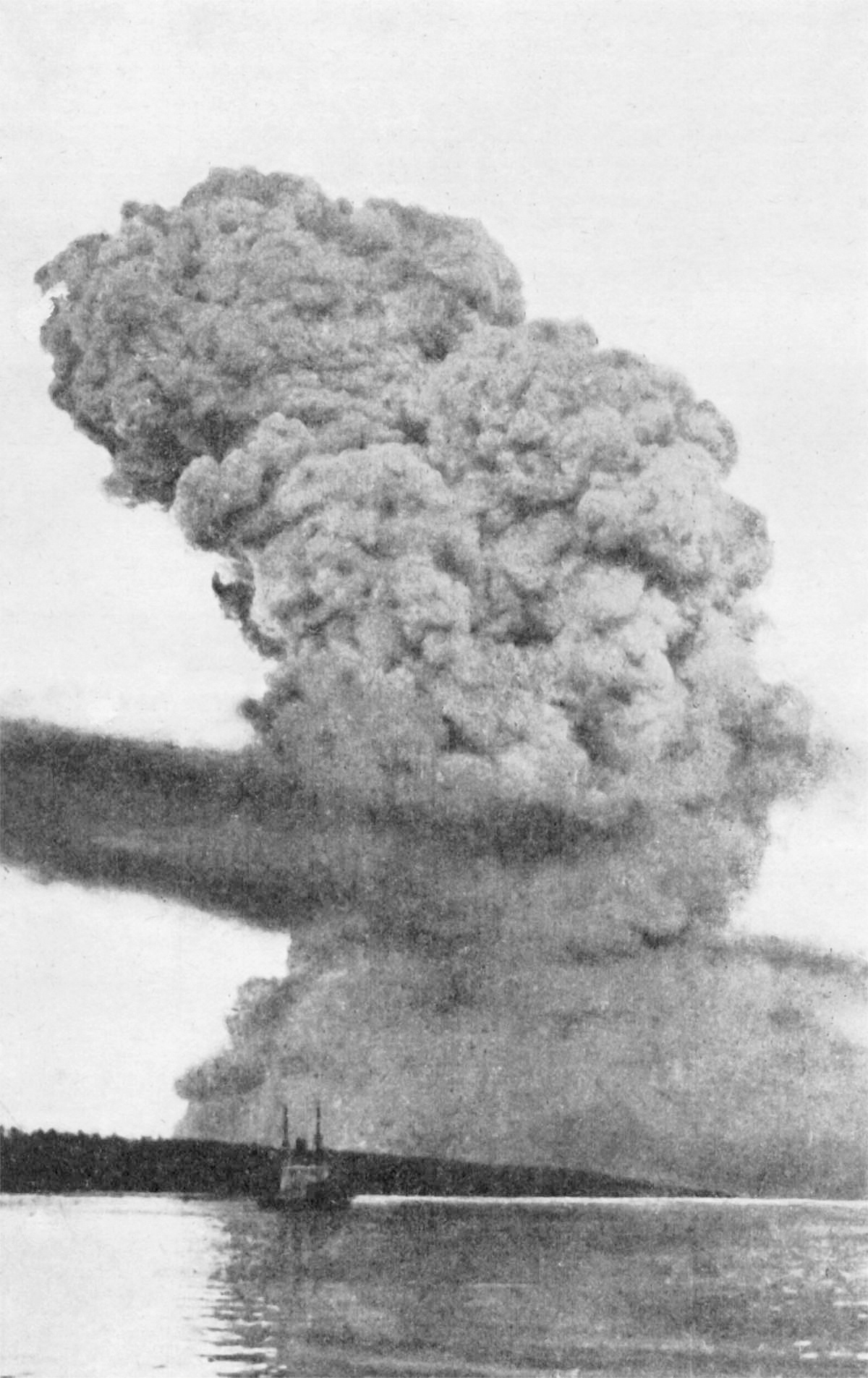

Born in Nova Scotia in 1884, Edith Keating was the eldest of five children. She attended Halifax Ladies’ College, but her life truly began taking shape during moments of upheaval. At age 33, she survived the Halifax Explosion of 1917, a devastating blast that killed nearly 2,000 people—including her own grandmother—and injured thousands more. Keating was thrown 50 feet by the force of the explosion and hit by a wooden beam. Local accounts claims the trauma was so severe it turned her brown hair white overnight.

Following the tragedy, Keating set out across the United States. She drifted through 43 states, working as a government stenographer, running tea rooms, and weathering everything from Texas tornadoes to California earthquakes. But it wasn’t until she reached New York City that she stepped into the field that would define her: aerial photography.

From the desk to the cockpit

What was supposed to be a stable office job at Fairchild Aerial Surveys quickly became the launchpad for an unlikely career. Fairchild specialized in mapping and aerial imaging, and Keating found herself magnetically drawn to the photographs that lined its offices. By her own account, she was a terrible stenographer—far more interested in cameras than clerical work.

So she made a request that few women of the 1920s would dare: to join the men in the air. Her first flight over Long Island was a bust. She panicked, took no photos, and spent the ride believing she was about to die. The next day, she went up again. This time, she managed to click the shutter. By her third attempt, she had a usable photograph of Little Neck, and Fairchild had a new kind of asset on its hands.

Within a few years, Keating had earned the trust of Fairchild’s executives and began flying regular missions. She operated massive, 50-pound aerial cameras from open cockpits and captured striking views of cities from above. In one standout flight, she ascended 16,000 feet over Manhattan to photograph the city from a bird’s-eye perspective. Her 1928 image revealed skyscrapers bathed in sunlight, the rivers cutting silver paths around the island, and Central Park nestled like a green stamp amid the sprawl. It remains one of the earliest known aerial cityscapes of New York credited to a woman.

A nod from Amelia Earhart

Keating’s achievements caught the attention of another trailblazer. In 1929, Amelia Earhart mentioned Keating in her Cosmopolitan column, calling her a pioneer in aerial mapping. She applauded Keating’s technical skill and courage—particularly her unusual role as both a field photographer and Fairchild sales executive. That dual position, Earhart suggested, was proof that women could do more than hold office jobs: they could shape the infrastructure of aviation itself.

At Fairchild, Keating had risen to assistant manager, one of the few women in such a role at the time. Her success wasn’t a one-time headline; it was day-to-day persistence, professionalism, and output.

Keating’s work wasn’t easy. Aerial photography in the 1920s was cold, loud, and physically grueling. She flew in open cockpits, battling wind, vibration, and unpredictable air currents while wrestling with oversized cameras. The margin for error was razor-thin.

She also faced the doubts and quiet resistance of colleagues. Her supervisors hadn’t hired a flier. But over time, the photos spoke louder than the skepticism. Keating didn’t make a fuss. She just kept showing up, kept flying, and kept delivering results.

Building a new view of the world

Keating helped transform aerial photography from novelty to necessity. Her images were more than beautiful; they were also functional. Cities used them for urban planning. Developers used them to map out future builds. Her work showed what aerial imaging could accomplish long before satellites or drones entered the picture.

After leaving Fairchild in the early 1930s, she remained active in aviation. In the 1940s, she led the Manhattan chapter of Woman Flyers of America, advocating for the inclusion of women pilots in wartime service.

Edith Keating died in 1952 at the age of 68. She never achieved household-name fame like Earhart, but her mark on the history of photography and aviation is undeniable. She viewed the world through a lens few had access to, and she left behind a body of work that helped reshape how we see cities, land, and the possibilities above us.

Today, aerial imagery is everywhere. It guides our navigation apps, sells real estate, and supports disaster response. A century ago, Edith Keating was leaning out of a biplane, capturing the world below with nothing but a camera and a steady hand.

Fun Fact: Much of our oldest imagery around New York and New Jersey are from Fairchild Aerial Surveys and likely includes work done my Edith Keating. Check out these and other imagery on our Viewer at HistoricAerials.com.