Aerial Perspectives on the Francis Scott Key Bridge History

Steel folded like paper, concrete sheared into jagged edges — the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge left a visual imprint that’s hard to forget. News coverage delivered every angle from ground level and above, but even in those first hours, one thing felt missing: a view stretching back before the bridge existed at all. That’s where the Francis Scott Key Bridge history aerials reveal something the breaking-news cameras never could — the long arc of how this crossing came to be.

Historic Aerials holds imagery of Baltimore’s outer harbor reaching as far back as 1957. In those frames, you see not just the footprint of a future bridge, but a piece of regional planning that took two decades, a few political fights, and one major pivot to finally take shape.

The Outer Harbor Before the Bridge

The 1966 aerial makes something immediately clear: there was no outer harbor crossing — not even the hint of one. What you see is a wide, uninterrupted sweep of the Patapsco River between Hawkins Point and Sollers Point. By then, local and state officials were already deep into conversations about an east-west connection that could relieve congestion on the older Harbor Tunnel and complete the beltway loop encircling Baltimore.

This was the era when the Baltimore region’s transportation planning shifted from one-off fixes to long-term, big-picture infrastructure. The outer harbor crossing was meant to be the project that tied everything together, forming the final missing link along I-695.

Why the First Plan Was a Tunnel, Not a Bridge

In the early planning stages, a bridge wasn’t even on the table. Maritime interests — especially shippers who relied on access to the port’s deeper terminals — feared a bridge would someday limit vessel size or create navigational bottlenecks. Political pressure followed, and the initial legislation authorizing bond financing required that the new crossing be a two-lane tunnel.

That decision looked routine at first. Then the bids arrived.

The construction estimates for a tunnel came back far higher than expected, blowing past budget projections and threatening to stall the entire project. The State Roads Commission was forced into a difficult but necessary question: was a tunnel still the best way forward?

Cost, not design philosophy, opened the door to a radically different solution.

The Aerial Clue: Causeways Built for the Wrong Project

Even as the tunnel debate dragged on, construction crews pushed ahead with work on two long embankments extending from each shoreline. These weren’t speculative experiments — they were built specifically for a submerged tunnel alignment. But engineers left themselves an escape hatch: the causeways were designed so that if the plans changed, they could be repurposed for a bridge.

In the 1971 aerials, those causeways appear as geometric fingers reaching into the Patapsco. It looks like a bridge project already underway, even though on paper the crossing was still technically a tunnel. That single image says more about Maryland’s political and engineering balancing act than most reports ever captured.

Reevaluating the Project: From Tunnel to Bridge

Once the tunnel bids shattered the financial model, state officials began a top-to-bottom reanalysis. Could a bridge be built instead — and could it be done within the same general footprint?

The answer landed in favor of the bridge. The design was revised into a four-lane steel cantilever bridge, significantly boosting traffic capacity over the originally planned two-lane tunnel. The causeways, already in place, became the backbone of the approach spans. What had been the start of a tunnel suddenly became the first chapter of a bridge.

Building the Francis Scott Key Bridge

Construction broke ground in August 1972. Historic photos from the era show steel crawling upward from those earlier embankments, the framing extending over water that had never hosted anything more than barges and small working vessels. The transformation didn’t just reshape the shoreline — it reoriented how the greater Baltimore region connected with itself.

It took nearly five years to complete the structure. When the bridge opened in March 1977, it carried more than commuters. It carried a new identity for the outer harbor, one where industrial landscapes, port facilities, and neighborhoods on opposite sides of the Patapsco suddenly felt stitched together more tightly than ever.

The Bridge in Its Prime

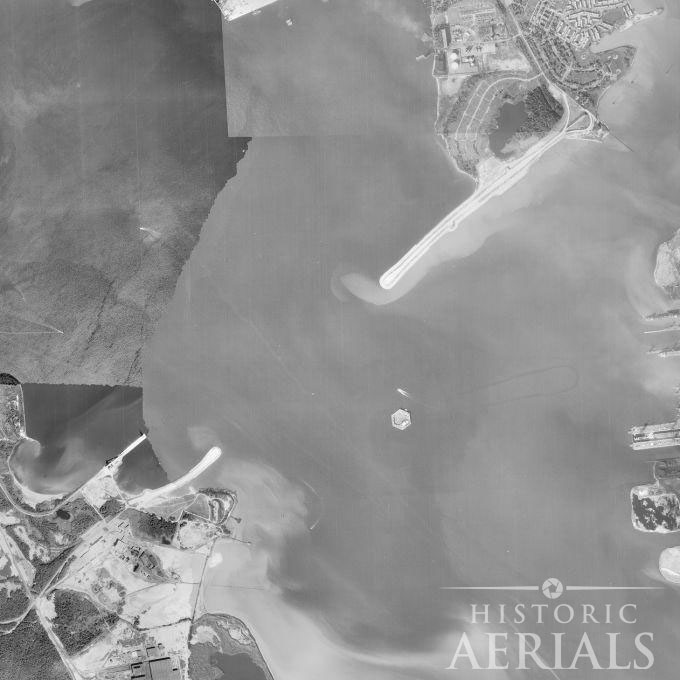

The 1981 aerial shows the bridge at its earliest full stride — slender, balanced, a long sweeping arc cutting across the water with the confidence of a structure meant to last generations. Industrial terminals curved around its approaches, trucks traced steady paths over its deck, and the ring of I-695 finally closed into a continuous loop.

For nearly half a century, the Key Bridge served as a vital artery for the region’s economy and daily life. Its role extended beyond convenience; it shaped trade routes, commutes, neighborhood developments, and the cultural geography of the city.

Through all that time, the aerials tell an evolving story: shipyards shifting, terminals expanding, new road networks branching outward. The bridge remained the anchor tying it all together.

A Landmark Lost, a History Preserved

The collapse may have brought the Key Bridge back into national conversation, but the structure’s larger story — the debates, the pivots, the engineering compromises, and the decades of traffic it carried — is still written across the landscape in ways only aerial imagery can reveal.

HistoricAerials helps place that story in its full arc. You can scroll backward through time and see a rising structure where there once was only open water, or watch the causeways appear before anyone knew a bridge was coming. These are the quiet details that turn raw infrastructure into human history.

Explore the Key Bridge’s Past Yourself

If you want to follow this transformation frame by frame — from untouched harbor to the first causeways to the completed span — explore the area using the HistoricAerials map viewer and trace the Key Bridge’s history from above.

Recent Articles

-

Public Domain Day 2026

Why 1930 Sanborn Maps are in now in the public domain…and how the rules actually work Every January 1, a quiet but meaningful shift occurs in the historical record. Another year’s worth of creative works (books, photographs, films, sheet music, and maps) cross an invisible legal threshold and become part of the public domain. On…

-

An Update on Our Free Viewer and Ad Blockers

Historic Aerials has always been built around a simple idea: historical aerial imagery should be easy to explore, searchable, and available to everyone. From the beginning, we’ve worked hard to offer a free version of the site so students, historians, planners, and the public can explore decades of aerial history without a paywall. But keeping…

-

The Reindeer’s Eye View: America’s Christmas Towns

Some places celebrate Christmas. Others were, according to local legend, named by it. Christmas Eve Origins In both Santa Claus, Indiana, and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, the stories begin on Christmas Eve.One legend tells of a small Midwestern town that gathered to rename itself, drawing inspiration from carols drifting in from a nearby church. In the other,…

-

Edith Keating: Aerial Photography’s First Woman Pioneer

In 1925, Edith Keating was hired to type memos at Fairchild Aerial Surveys in New York City. It was a standard administrative role, but Keating proved to be a distracted stenographer. Instead of focusing on her typewriter, she spent her time studying the aerial photographs pinned to the office walls. Within months, she traded her…

-

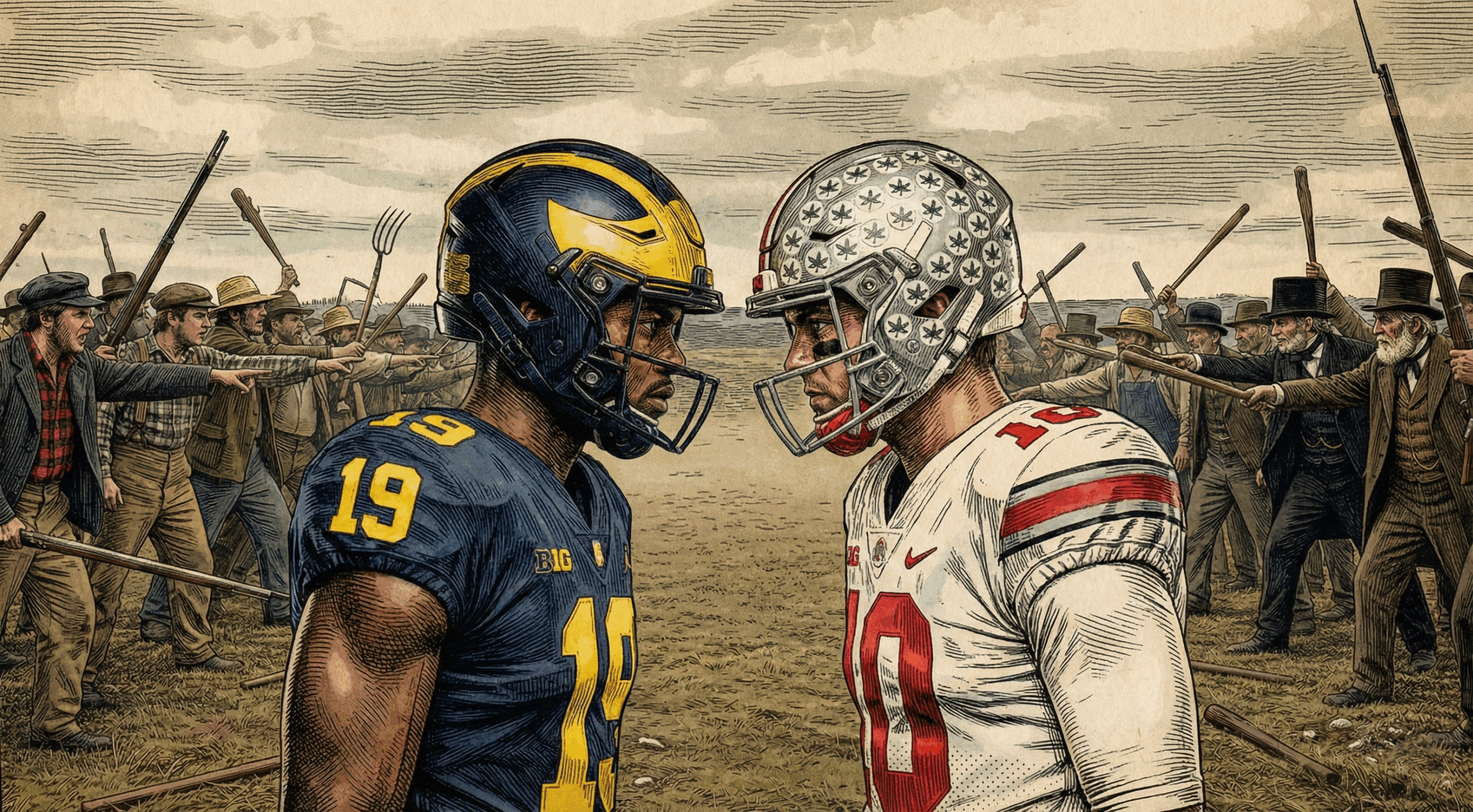

From the Toledo War to The Game: How a Misdrawn Map Fueled the Michigan–Ohio Rivalry

Three days from now, when Ohio State and Michigan line up for The Game, millions will tune in for a football rivalry. What they’ll actually be watching is the latest round in a border dispute that predates helmets, hash marks, and even the modern outline of the Midwest—a fight so petty, so strangely consequential, and…