Today, we take for granted the ability to access aerial images of almost any location in the world with just a few clicks. From satellite views to drone footage, these images are an essential part of modern life. However, capturing aerial photographs was once an arduous task, fraught with technical challenges.

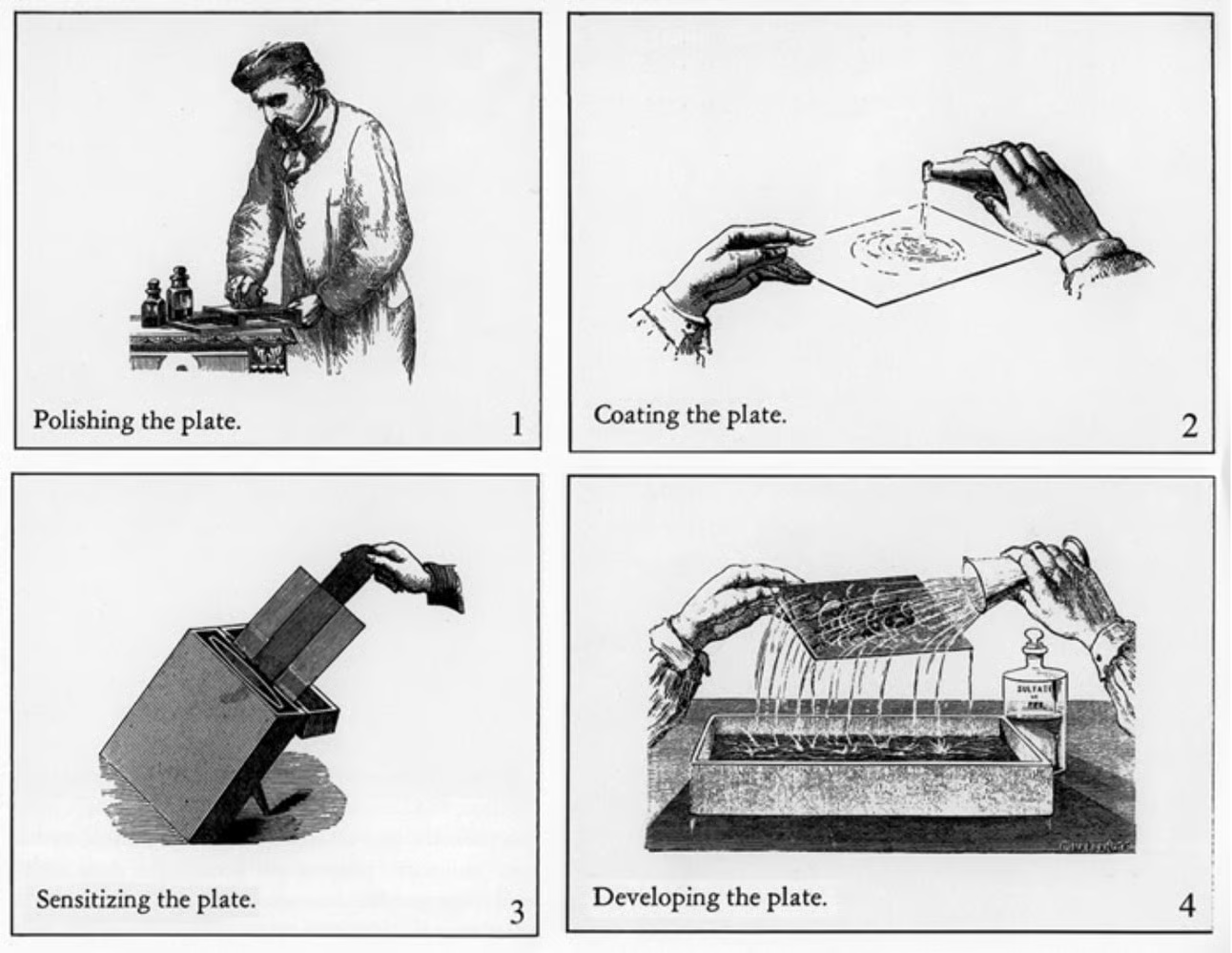

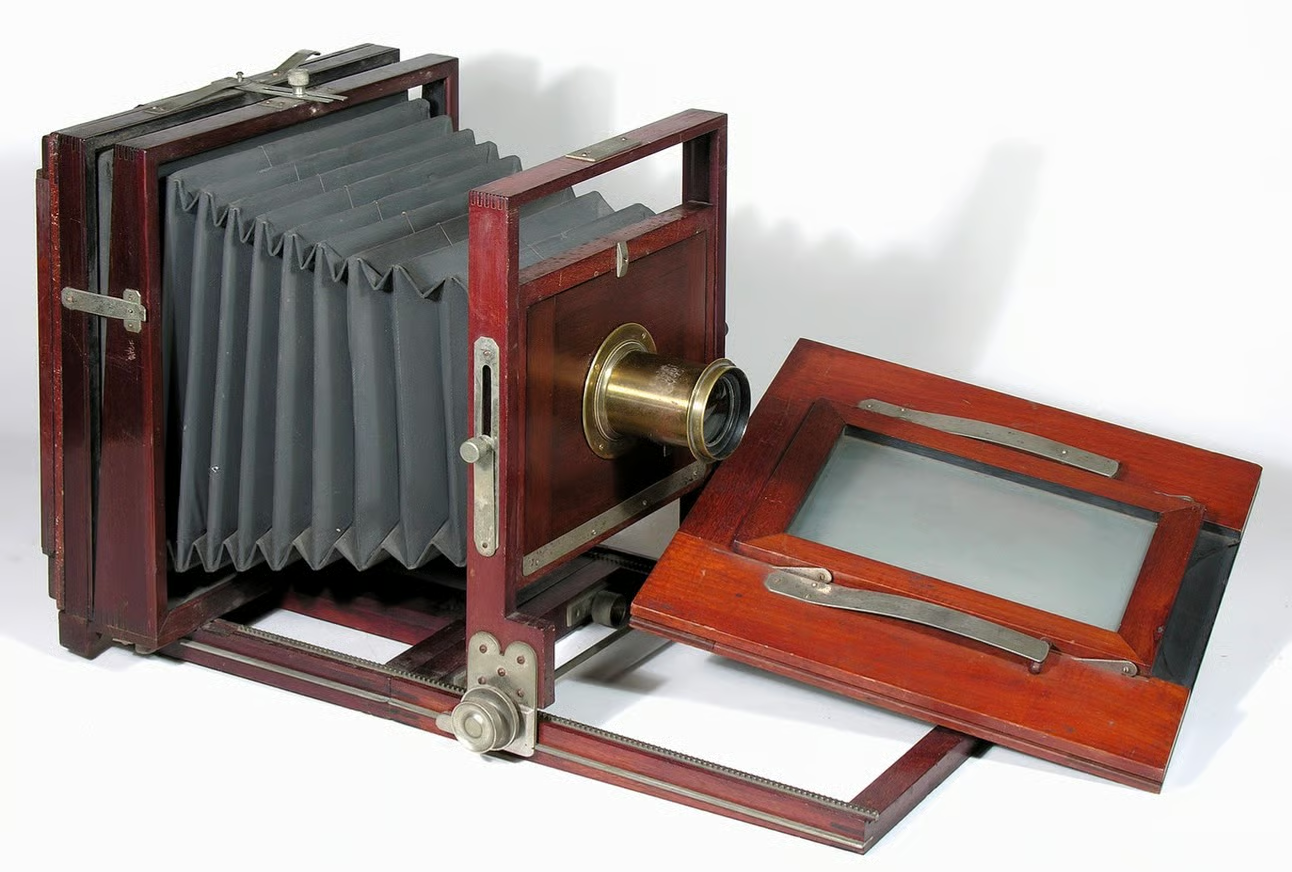

Early photographers relied on the wet collodion process, which demanded not only heavy equipment and immediate on-site development but also long exposure times—often several seconds or more. For aerial photography, where the camera and subject were constantly in motion, this was virtually impossible. The slightest movement of the balloon or kite could render the image blurry and unusable.

A breakthrough came in 1871 when British physician and photographer Richard Leach Maddox introduced the dry plate process. Unlike the wet collodion plates, which required rapid development, dry plates were coated with a gelatin emulsion that allowed them to be prepared in advance, stored for long periods, and developed later. More importantly, they were far more sensitive to light, dramatically reducing exposure times. This made it feasible to capture sharp images even in unstable conditions, such as those encountered in aerial photography.

With the introduction of dry plates, aerial photography became practical for the first time. Photographers could take multiple images during a single flight without the logistical nightmare of carrying chemicals and portable darkrooms aloft. This revolutionized how landscapes were documented, enabling the use of aerial photography in cartography, military reconnaissance, and archaeological exploration.

Since then, photographic technology has continued to advance—from roll film to digital sensors to high-resolution satellite imagery. Today, aerial photographs are used in urban planning, disaster management, environmental monitoring, and even entertainment. Yet, it was the dry plate process that acted as the catalyst for this progress, overcoming the limitations of early methods and laying the foundation for the ubiquitous aerial imagery we now rely on every day.