Three days from now, when Ohio State and Michigan line up for The Game, millions will tune in for a football rivalry. What they’ll actually be watching is the latest round in a border dispute that predates helmets, hash marks, and even the modern outline of the Midwest—a fight so petty, so strangely consequential, and so baked into the landscape that it still echoes in county maps, freeway exits, and one thin strip of land that never should have mattered but somehow still does.

It all started with a bad map.

Before the Michigan-Ohio State Rivalry: Ohio’s Chaotic Survey System

Long before anyone picked up a football in Columbus or Ann Arbor, Ohio was already a national experiment—a proving ground for how the United States would divide, sell, and settle the West. The Public Land Survey System (PLSS), the grid that would eventually stamp its neat geometry across most of the American interior, got one of its earliest and most chaotic test runs right here.

Ohio is unique: it wasn’t surveyed under one tidy plan. It was surveyed under seven!

Seven incompatible, overlapping, often contradictory systems—each reflecting a different moment of federal improvisation.

Tilt over eastern Ohio and you’ll notice the irregular, diagonal grid of the Seven Ranges—America’s first federal survey (1785). Move west, and the lines suddenly reshape themselves into the tidy, rectangular townships familiar across the Midwest. Then swing north and watch everything go crooked again, thanks to Connecticut’s Western Reserve, which used yet another system entirely. Even the numbering changes: some townships start at “1” in the north, others in the south, others in the east. It’s a surveyor’s fever dream.

All of this left Ohio with something no other state possesses: a patchwork of survey regimes that made borders harder to define, land claims harder to manage, and political nerves easier to jangle.

Including—unfortunately—the nerve that led straight to Michigan.

The Disputed Border That Sparked the Michigan-Ohio State Rivalry

In 1787, when Congress carved the Northwest Territory, it set the future Ohio–Michigan line as an east-west stretch drawn from the southern tip of Lake Michigan to Lake Erie. The problem? Congress relied on a map that placed Lake Michigan too far north.

If those maps were right, the boundary would hit Lake Erie above the mouth of the Maumee River.

If the real geography prevailed, that same line would land below the river—kicking the future city of Toledo into Michigan.

Ohio’s founders weren’t amused. Losing the Maumee meant losing a future port, a canal terminus, and a chunk of economic destiny. So when drafting the state constitution in 1802, they added a clause: if the old maps turned out to be wrong, Ohio’s border would tilt northeast to ensure the Maumee—and Toledo—stayed in Ohio.

Michigan, organized as a territory in 1805, rejected that… strongly. The federal government kept using the original Ordinance Line in its descriptions. Two incompatible borders, both rooted in the nation’s earliest surveying chaos, now overlapped like a badly placed transparency.

The stage was set.

The Toledo War: The Michigan-Ohio State Rivalry’s Forgotten Origin

By the 1830s, both governments had drawn competing survey lines—the Harris Line for Ohio, the Fulton Line for Michigan. Between them sat a skinny 468-square-mile strip of swamp, forest, and illusionary prestige: the Toledo Strip.

Michigan wanted it.

Ohio needed it.

Nobody was willing to blink. So the militias were called up.

Michigan’s 23-year-old governor, Stevens T. Mason—nicknamed the “Boy Governor”—signed the Pains and Penalties Act, threatening jail time for any Ohio official operating in the strip. Ohio governor Robert Lucas responded by mobilizing thousands of volunteers. Muskets were loaded. Lines of battle were drawn.

No one actually fired a shot… unless you count the Michigan sheriff who got stabbed in the backside with a penknife by Two Stickney, the son of an Ohio partisan. That tiny stabbing is still the only recorded casualty of the “war.”

But the drama, the rhetoric, the mobilization—it all stuck.

Ohio won the strip. Michigan got the Upper Peninsula as consolation. And the two neighbors quietly began nursing a brand-new cultural grudge.

How the Michigan-Ohio State Rivalry Moved From Militias to Football

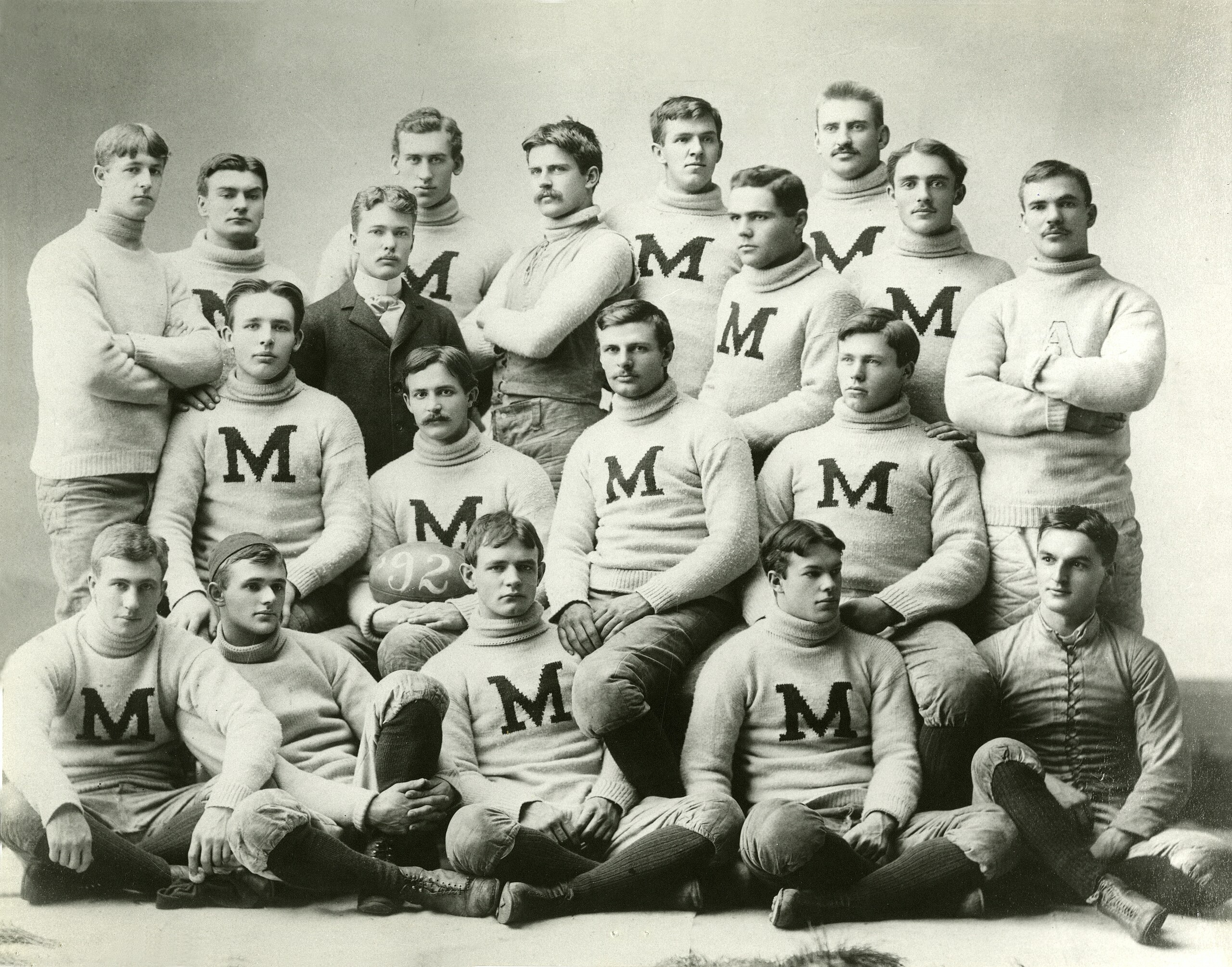

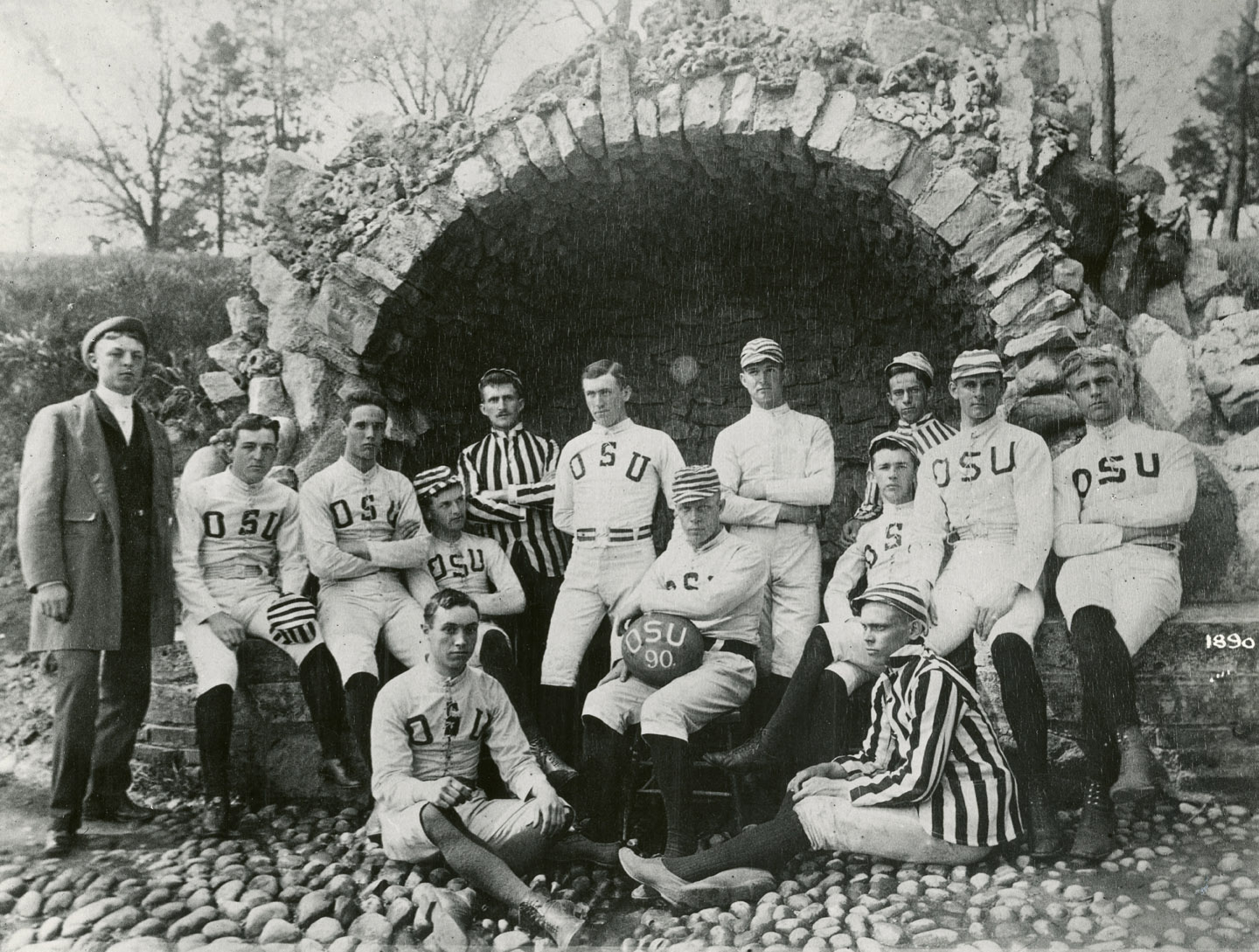

It’s no accident that when Ohio State and Michigan first met on the football field in 1897, people immediately sensed a certain… familiarity. One newspaper joked Michigan was “still trying to reclaim Toledo, six points at a time.”

That first game ended 34–0 for Michigan.

The rematch—the one we’ve been replaying every November for more than a century—never really ended.

Over time, football became the great pressure valve for a rivalry that once sent militias tramping through the Black Swamp. Everything the Toledo War once symbolized—identity, pride, borderlines, bragging rights—shifted onto the turf.

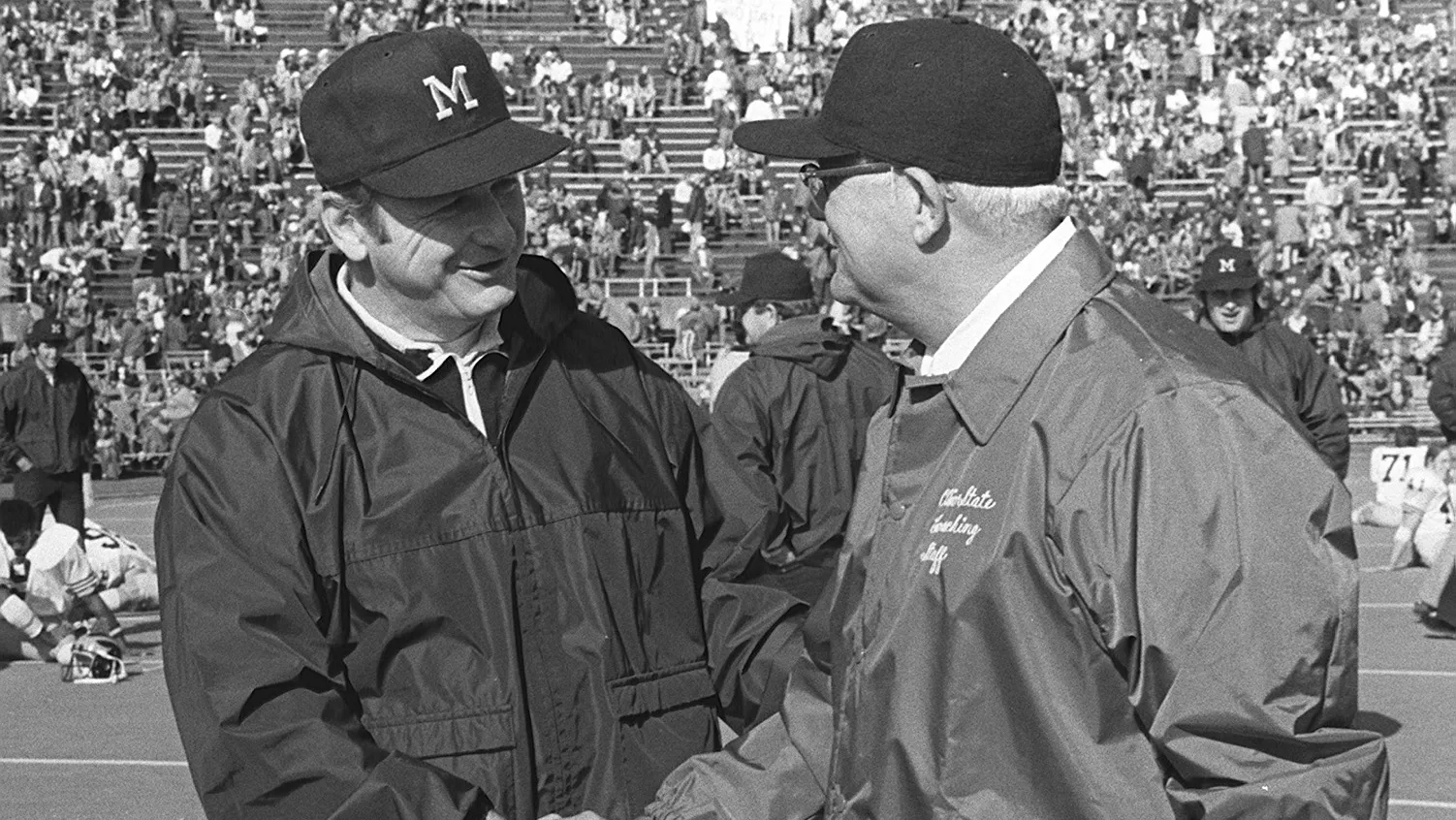

In the 1970s, Woody Hayes and Bo Schembechler reenacted the whole saga as a ten-year proxy war. From 1969 to 1978, their teams traded blows in what became known as the “Ten-Year War” that seemed more like a referendum on which side of the old Ohio–Michigan divide really “owned” the Midwest: low‑scoring slugfests, controversial calls, bitter postgame quotes, and seasons defined by a single Saturday in late November.

Ohio State sees itself as the gritty populist brawler; Michigan sees itself as the refined intellectual powerhouse. Both are convinced they’re the rightful heirs to Midwestern supremacy. And every year, “The Game” becomes the ritual settling of accounts.

Even the little traditions echo the old fight:

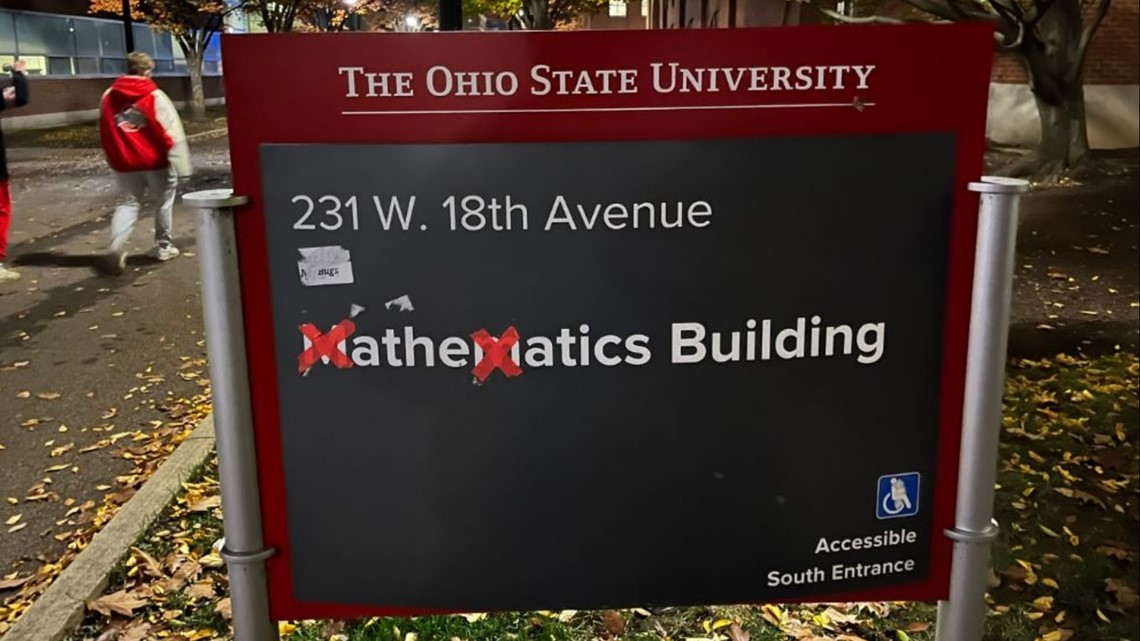

- Ohio State crosses out every “M” in Columbus during rivalry week.

- Michigan refuses to say “Ohio State,” sticking with the more dismissive “Ohio.”

The governors of both states make wagers, as if reenacting diplomatic negotiations. (Although that tradition may be on hold for now.)

And in Toledo—the city everyone once bickered over—you’ll still find families split down the middle.

And Now Here We Are, Three Days Before Kickoff

Nearly 190 years after two states nearly drew blood over a patch of wetland and a surveyor’s compass, we’re still arguing—thankfully now with touchdowns instead of treaties.

When Ohio State and Michigan step onto the field this Saturday, they’ll be carrying a rivalry that predates barbed wire, predates the Civil War, predates the modern map of the Midwest. A rivalry born not from athletics, but from the wild, experimental birth of America’s public land system—and the messy human decisions that followed.

So if the game feels personal this weekend, if the cheers feel a little louder or the nerves a little sharper… well, they should. This isn’t just a football game.

It’s the latest entry in a long, strange, beautifully American argument over who gets to claim what—and why it matters.

More Time & Place: Historical Narratives

-

Christmas Towns in America: Santa Clause, IN and Bethlehem, PA

Christmas Eve Origins Some places celebrate Christmas. Others were, according to local legend, named by it. Among the most distinctive Christmas towns in the United States are Santa Claus, Indiana and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania—and in both, the stories begin on Christmas Eve. One legend tells of a small Midwestern town that gathered to rename itself, drawing…

-

The Secret Places Where New Cars Are Sent to Be Broken

As a new resident of Arizona, I’ve spent some time scrolling through aerial imagery of the surrounding landscape, examining the evolution of cities like Phoenix, Tempe, and Mesa over the decades. This week, I spotted something I hadn’t seen before—a large circular track etched into the desert floor, flanked by smaller ovals, long narrow loops,…