Many of America’s earliest airfields and airports are now decommissioned or repurposed. Looking at modern satellite imagery, you might never know they existed without a closer examination of a place’s history. However, historic aerial imagery still holds traces of some of the most historic airfields, compelling further investigation.

Let’s take a look at some of the most significant historic airfields and what became of them.

Roosevelt Field (Long Island, New York)

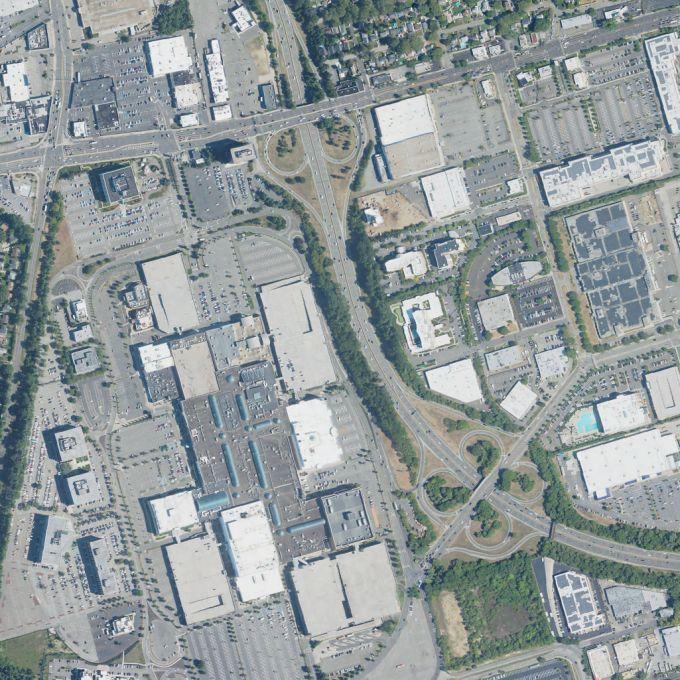

Roosevelt Field was a famous airfield in East Garden City (Uniondale) on Long Island, New York. It started as Hempstead Plains Aerodrome—a World War I Army Air Service training field known as Hazelhurst Field. In 1919, the field was renamed Roosevelt Field to honor Quentin Roosevelt (President Theodore Roosevelt’s son, killed in WWI air combat).

During the 1920s and ’30s, Roosevelt Field grew into one of the nation’s most prominent civilian airports. In fact, it was the takeoff point for many historic early flights. Most famously, on May 20, 1927, Charles Lindbergh departed Roosevelt Field on his solo Spirit of St. Louis flight across the Atlantic—the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight in history. Aviation pioneers like Amelia Earhart and Wiley Post also used Roosevelt Field for record-setting flights. At its peak in the 1930s, it was reportedly the busiest civilian airfield in America.

The airport served as a naval and Army air station during World War II, returning briefly to civilian use afterward before its closure. Post-war commercial operations proved short-lived. Real estate developers purchased the land in 1950, and the airport officially closed on May 31, 1951.

The historic field soon transformed dramatically. Part of the eastern airfield became an industrial park and later retail centers (such as The Mall at The Source built roughly over a former runway). The western section—including the original 1910s flying field—is now the site of the large Roosevelt Field Mall shopping center. A modern commercial hub now occupies the very ground from which Lindbergh and others once roared into the sky.

Learn more about the history of Roosevelt Field.

Grand Central Air Terminal (Glendale, California)

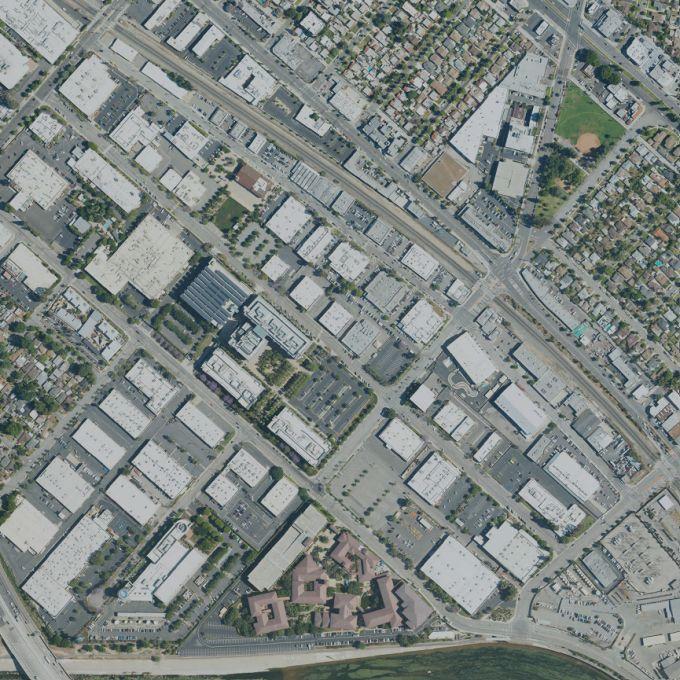

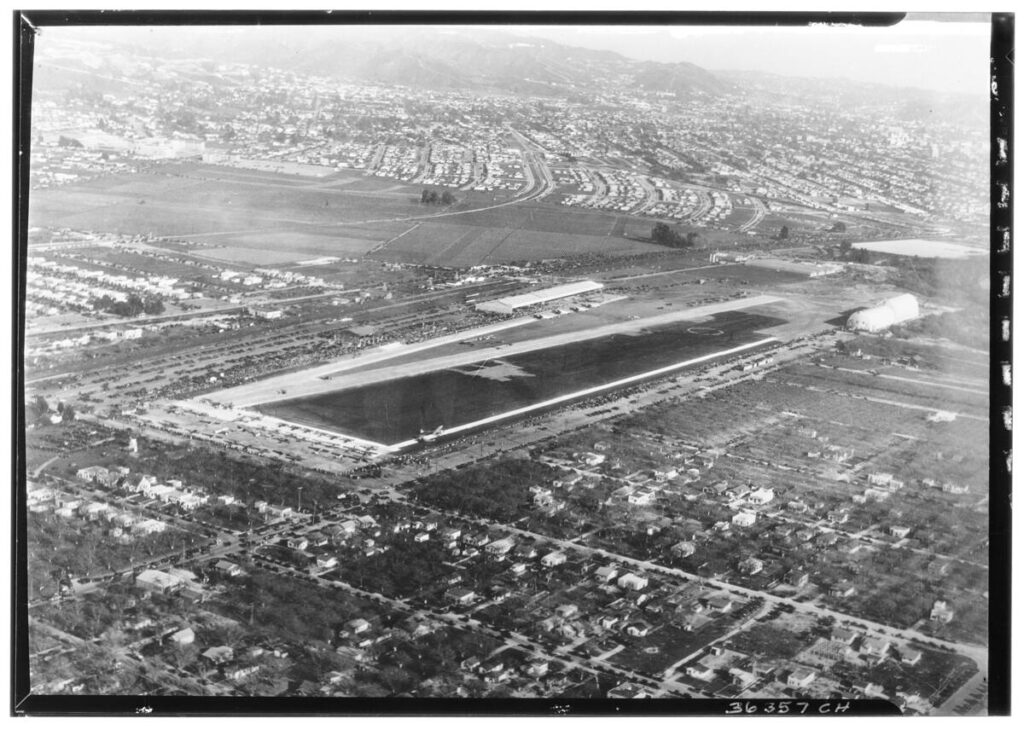

The Los Angeles area was the cradle of aviation on the West Coast. Grand Central Air Terminal (GCAT) in Glendale was a pioneering airport that no longer operates, but whose site and buildings still stand. Grand Central opened in 1929 as the first commercial airport for the growing Los Angeles metropolis.

A West Coast Aviation Hub

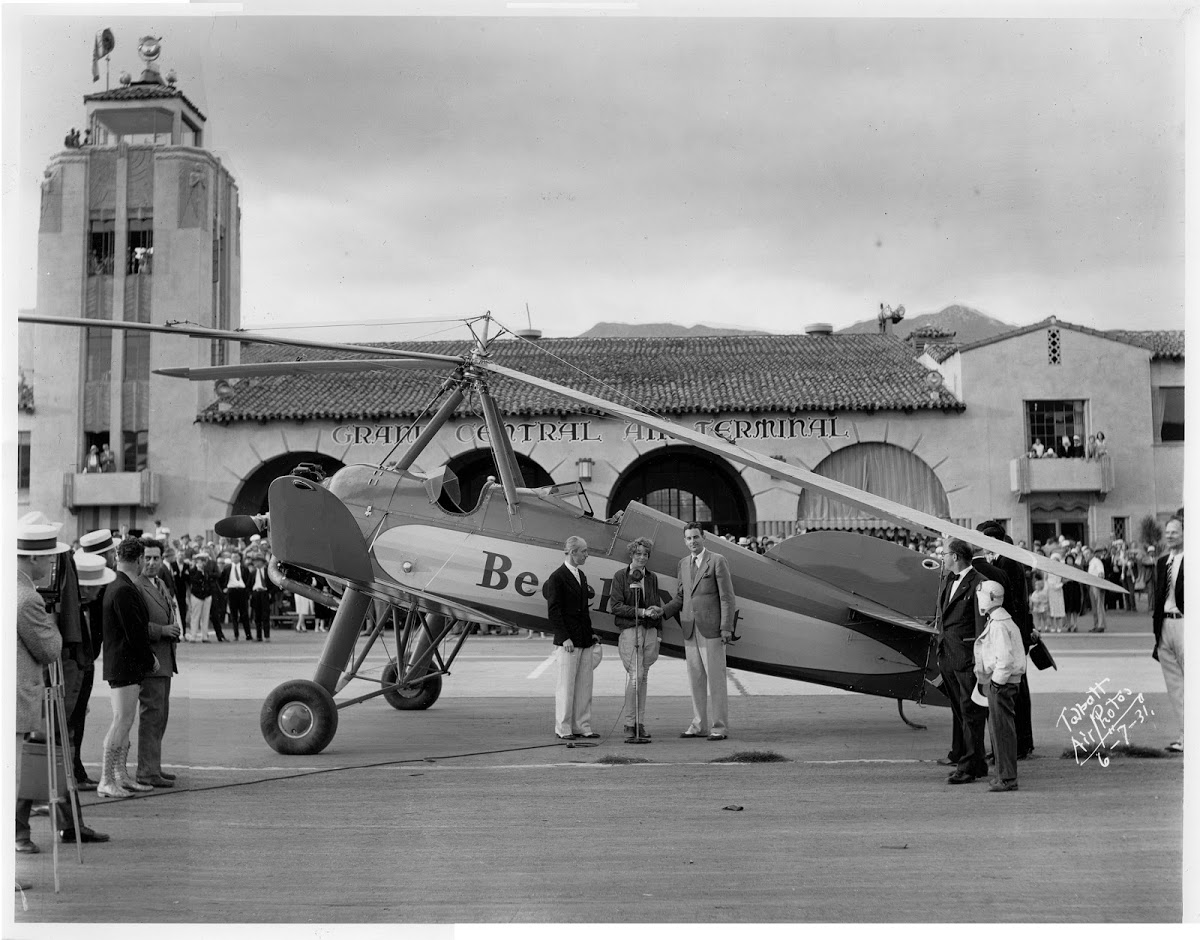

Its beautiful Spanish Colonial Revival / Art Deco terminal building (1310 Air Way, Glendale) was state-of-the-art and still survives today. The building is now restored and listed on the National Register of Historic Places. During the 1930s, Grand Central Air Terminal was the aviation hub of Southern California, witnessing numerous milestones in civil aviation.

Grand Central played a central role in early airline history. In 1929, Charles Lindbergh himself piloted the nation’s first regular coast-to-coast airline flight from Glendale, as part of Transcontinental Air Transport (which later became TWA). Many aviation pioneers also used the airport as their home base or testing ground. Amelia Earhart frequented the field and even purchased her first airplane there. In 1930, Laura Ingalls completed the first female solo transcontinental flight when she landed at Grand Central Air Terminal.

In 1933, pilots Albert Forsythe and Charles Anderson became the first African Americans to fly transcontinental (from Atlantic City to Glendale). This achievement helped pave the way for the Tuskegee Airmen. The airport was a hive of innovation: Howard Hughes built his record-setting H-1 Racer in a hangar by the field in 1935, and Jack Northrop and William Boeing both established aircraft manufacturing ventures on-site in the late 1920s. Early airlines including Western Air Express and Varney Air Lines operated from Glendale. After mergers, the site became a hub for Trans World Airlines (TWA).

Decline and Legacy

Grand Central’s prominence declined after the late 1930s as newer airports like Burbank and Los Angeles Municipal (LAX) expanded. During World War II, the military requisitioned the airport, camouflaging it for use as a training base and aircraft modification center.

After the war, it returned to civilian use but faced pressure from suburban growth. The runway was shortened, and airlines had already moved out. By the 1950s, the facility was underutilized and struggled financially. The airport’s owners announced its closure in 1959, and Grand Central Airport shut down operations that year. Developers then redeveloped much of the Grand Central property into the Grand Central Business Park.

In the 1960s, the Walt Disney Company purchased a large portion of the site. Today, the old terminal is preserved as part of Disney’s Grand Central Creative Campus, serving as offices and an event space after an award-winning restoration. A few original hangars also remain. Visitors can still see the elegant terminal facade and imagine the days when Glendale’s Grand Central Air Terminal was the bustling heart of West Coast aviation, sending off DC-2s and welcoming intrepid air travelers in the early 20th century.

Learn more about the history and restoration of Grand Central Air Terminal.

Crissy Field (San Francisco, California)

Crissy Field is a former airfield on San Francisco’s northern shore. It dates back to the earliest years of military aviation. Opened in 1921 as an Army airfield, Crissy Field became the West Coast’s first permanent Army air base and served as the Bay Area’s aviation center in the 1920s.

Pioneering Flights and Records

The field was named in honor of Major Dana H. Crissy, an Army aviator who died in a 1919 aircraft crash during a transcontinental air race. Crissy Field’s location by the Golden Gate made it a dramatic and strategic flying ground. It had a single grass runway (about 3,000 feet) and a row of hangars and barracks along the waterfront.

In its heyday, Crissy Field was the staging point for several aviation “firsts” and record attempts. In June 1924, a U.S. Army Air Service plane flew from Long Island to San Francisco in one day, marking the end point of the first successful dawn-to-dusk transcontinental flight across the United States. Later that year, the Army’s team for the first aerial circumnavigation of the globe stopped at Crissy Field during their journey. One of Crissy’s own stationed pilots, Lt. Lowell Smith, helped lead the round-the-world fliers upon their return.

Crissy Field also served as the launch site for early attempts at long-distance flights over the Pacific. In 1925, two Navy PN-9 seaplanes took off from Crissy in the first try at a flight from California to Hawaii (one ran out of fuel and was rescued at sea). Two years later, in 1927, Lieutenants Lester Maitland and Albert Hegenberger staged from Crissy Field before making the first successful nonstop flight to Hawaii (departing from Oakland in the Bird of Paradise). Crissy’s role in these pioneering efforts cemented its place in aviation lore.

Decommissioning and Restoration

Several factors eventually rendered Crissy Field obsolete for frontline use. Frequent fog and wind from the Golden Gate often hampered flying. Also, the field’s short runways could not accommodate the newer, heavier aircraft of the 1930s. Additionally, the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge nearby complicated the airspace.

Several factors eventually rendered Crissy Field obsolete for frontline use. Frequent fog and wind from the Golden Gate often hampered flying. Also, the field’s short runways could not accommodate the newer, heavier aircraft of the 1930s. Additionally, the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge nearby complicated the airspace.

In 1936, the Army opened Hamilton Field in Marin County, a larger, more inland air base, and Crissy Field ceased to be a primary air corps station. Military flying continued at Crissy on a smaller scale (for liaison planes and training) into the 1940s. Army helicopters even used it into the early 1970s for hospital evacuations during the Vietnam War era. Ultimately, the Presidio was decommissioned as an Army post in 1994, and Crissy Field was turned over to the National Park Service.

By the late 1990s, Crissy Field had become a forlorn expanse of asphalt, rubble, and derelict structures. However, a bold reclamation began between 1997 and 2000. Workers reshaped more than 230,000 cubic yards of fill over a 100-acre site to recreate 40 acres of vibrant habitat. The project featured an 18-acre tidal marsh and 22 acres of dunes and swales that reconnected the land to the bay and revived centuries-old ecosystems.

Learn more about the history of Crissy Field.

The Past Beneath Us

A century ago, these places rattled with radial engines and smelled of oil, dust, and courage. Now they hum with commerce and conversation—shopping malls, offices, parkland. The roar is gone, but the names remain: Roosevelt Field, Grand Central, Crissy Field. They’re echoes that never quite faded, reminders of a time when the sky itself was still an adventure.

So the next time you’re buying shoes on Long Island, walking past Disney’s offices in Glendale, or tossing a frisbee under the Golden Gate, take a second look. Beneath the pavement, the grass, the parking lots—you’re standing on runways.