In the pioneering days of aviation, navigating the skies was a challenging endeavor. Without modern instruments like GPS, pilots relied heavily on visual references and rudimentary navigation tools. The development of beacon stations played a crucial role in transforming air travel, providing essential guidance and safety for early aviators. In the 1920s and ’30s, a system emerged that would bring order to the chaos — an ambitious blend of cutting-edge radio waves and good old-fashioned concrete.

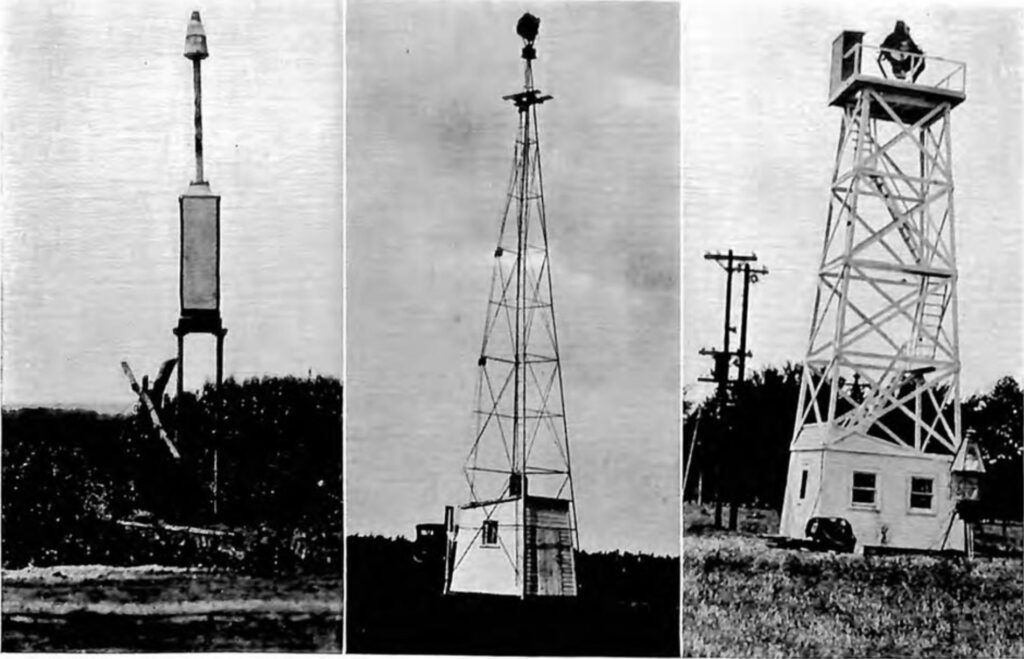

As aviation matured, so too did the need for structure. The U.S. Post Office Department and, later, the Department of Commerce, took the lead in building the infrastructure of the skies. Their solution was the airway beacon system — an innovative web of radio stations and illuminated towers that stitched together coastlines and crossed mountain ranges. These beacons transmitted Morse code signals that could be picked up by aircraft equipped with primitive radio direction finders, allowing pilots to triangulate their position in flight.

Yet technology alone didn’t conquer the sky. For those navigating by sight — especially in poor weather or at night — there was another tool, one that remains etched into the American landscape to this day: the concrete arrow. To guide pilots visually between beacon stations, particularly at night or in hazy conditions when radio signals might be weak, large concrete arrows were constructed on the ground, pointing towards the next beacon in the chain.

Source: Dreamsmith Photos

These arrows were massive, often stretching 50 to 70 feet in length and painted a bright yellow or orange to catch the pilot’s eye. Fixed directly into the ground and aligned toward the next beacon station, they formed a breadcrumb trail for pilots flying cross-country. Some arrows were paired with fifty-foot steel towers topped by rotating beacons — powerful acetylene or electric lights that pulsed a steady rhythm through the darkness, visible for miles.

A network of these stations emerged rapidly across the country. At their height, over 1,500 such beacons marked 18,000 miles of airway routes from New York to San Francisco. Each site required regular maintenance, with generators, caretakers, and rugged fieldwork keeping the system running in all conditions. In the process, a new kind of navigational culture was born — equal parts mechanical, cartographic, and heroic.

Many of these arrows can still be found scattered across the United States, albeit in varying states of disrepair. Some are well-preserved, with the concrete still intact and visible from the air. Others have been overgrown by vegetation, cracked by time, or partially destroyed by human activity. Many of these arrows are visible today in satellite imagery and historic aerial photography, standing out against fields, forests, and parking lots like ghostly compass needles.

GPS: 34.417009, -97.149813 Source: HistoricAerials.com

For historians and aviation enthusiasts, these arrows offer more than just nostalgia. They are physical coordinates of our aerial past — evidence that even in an age of signals and static, sometimes the most reliable guide is a literal point in the right direction. The concrete arrows of the airway beacon system are not just relics. They’re markers of the moment when human flight, once a daring novelty, began to scale up. With every arrow that still faces skyward, we trace the flight path of a nation learning to fly.