Stop complaining about your commute. Tomorrow morning, many of you will slide behind the wheel, your coffee securely nestled in its cup holder, climate-controlled air gently swirling around you, and your favorite radio show or podcast queued up to entertain your drive on smooth, reliable roads. Instead of bemoaning crazy drivers or traffic delays, take a beat to consider how good you have it. Imagine how arduous and painfully time consuming this same journey would have been just two centuries ago. Picture yourself wrestling a heavy wooden wagon over jagged rocks, axle-deep mud, and log roads that jolted bones loose and shattered wheels without mercy.

Early American journeys were brutal ordeals. Roads, where they existed, were rough and unpredictable. Take Braddock’s Road, for instance—a path originally hacked through dense wilderness by British General Edward Braddock during the French and Indian War in 1755. Narrow and littered with stumps and fallen trees, it was notorious for breaking wagon wheels and stranding travelers.

After Northwest Ordinance of 1787 provided for the creation of five States—ultimately named Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin—many, including George Washington, recognized a new problem to be addressed. The Allegheny Mountains divided the new country geographically and economically. To cross this mountain barrier meant risking life and limb, and even the simplest trips could stretch painfully into weeks. Settlers in the Northwest Territory had stronger trade ties to foreign powers than to the U.S.

While traveling the western territories in 1784, Washington wrote that settlers stood ‘as it were on a pivot’—ready to turn toward any power that gave them access to markets. Without reliable roads, their loyalty would follow trade routes, not borders. Yet, despite widespread acknowledgment of the urgent need for a reliable road, years of debate and political wrangling delayed its construction. The new nation grappled with competing regional interests, funding disagreements, and concerns over the federal government’s role in internal improvements.

Enter the Cumberland Road

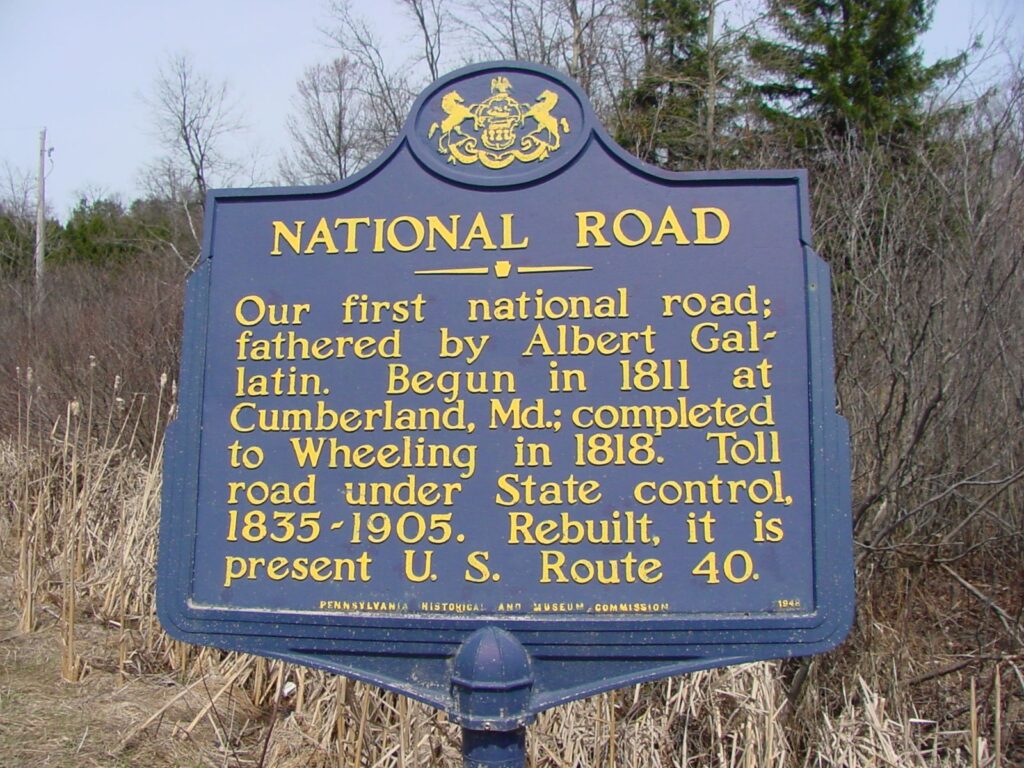

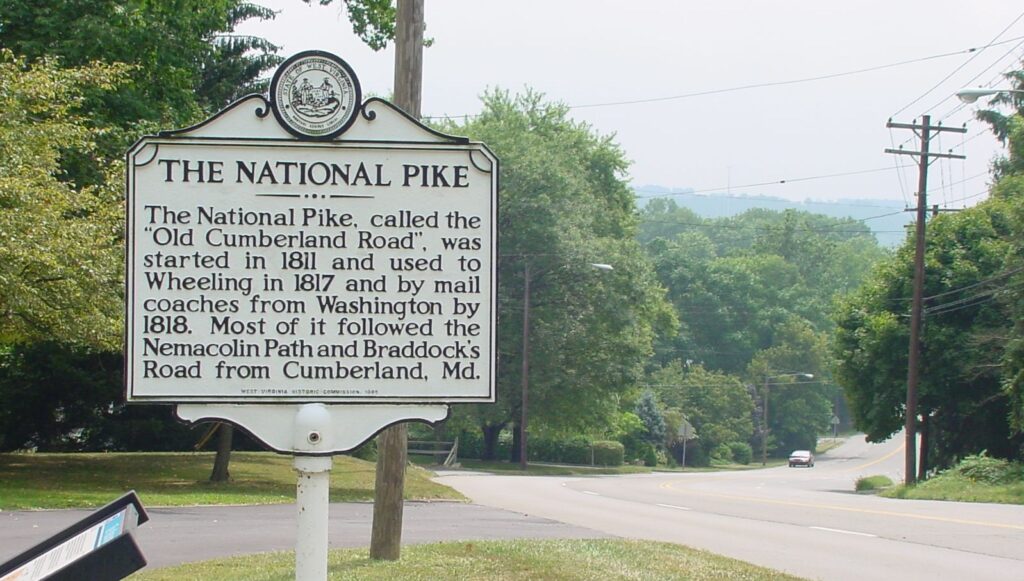

In 1806, Thomas Jefferson decided enough was enough. America needed a real road—one that connected the coastal states with their westernmost neighbors and tying together two halves of the nation. Congress finally approved construction of what was officially called the Cumberland Road, the first federally funded highway in U.S. history, a gravel thoroughfare stretching from Cumberland, Maryland, to the Ohio River. . It would also be referred to as the “National Road“, or “National Pike”.

Far from a rough clearing through the woods, this was a deliberate feat of engineering—graded, drained, and built to last. Graded slopes replaced steep inclines, and solid stone bridges arched gracefully over rivers once feared impassable. Cast-iron mileposts stood proud, marking progress and civilization amid the wilderness. Distances that once took weeks of hardship could now be traveled in mere days, without risking life, limb, or sanity.

Much of the earliest stretch of the Cumberland Road closely followed the route of Braddock’s Road. Though primitive and treacherous, Braddock’s Road had already revealed a viable corridor through the Alleghenies. By aligning with this existing trail, early engineers were able to adapt its course while improving the grade, widening the path, and replacing stumps and crude log bridges with engineered embankments and durable stone spans.

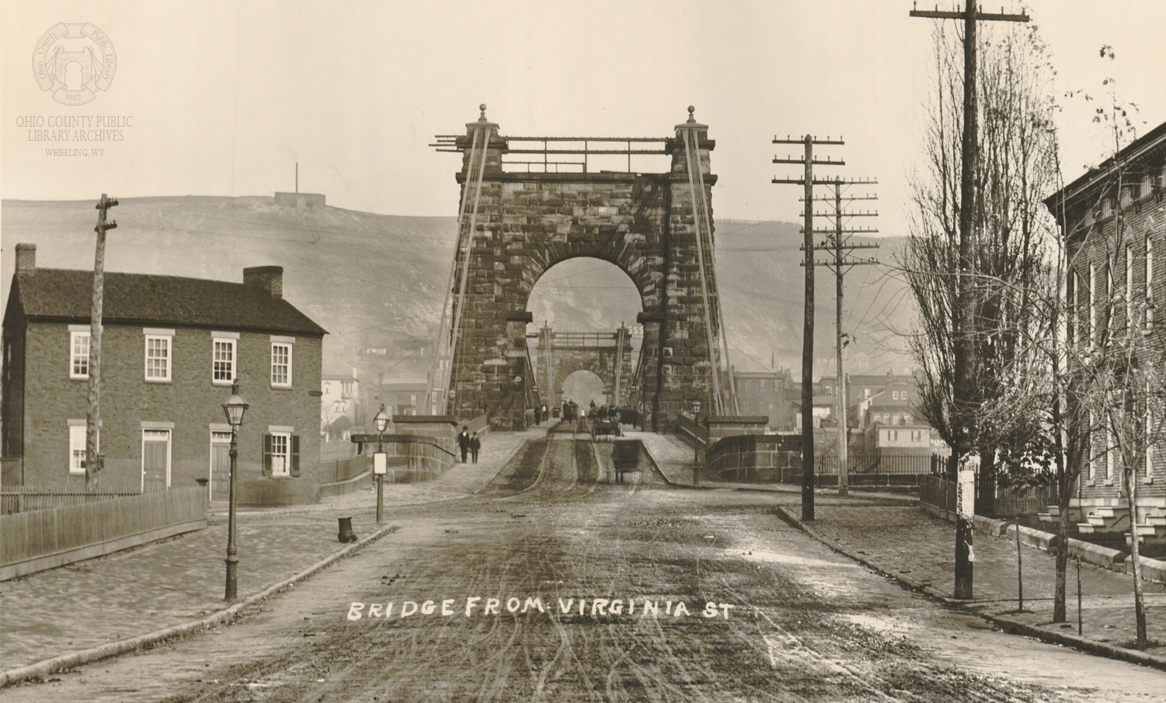

By 1818, this federally funded marvel had already reached Wheeling, then part of Virginia (now West Virginia), and was transforming America’s interior in ways few could imagine. Construction continued in stages for the next two decades, with the final segment reaching Vandalia, Illinois, in 1839—at the time, the edge of the American frontier. This marked the formal completion of the National Road, a trans-Appalachian artery that carried the nation westward, mile by painstaking mile.

The Road That Held Together

This pioneering road set standards for American highways we still rely on today. The graded slopes and engineered foundations influenced every modern roadway. One of the most significant innovations was the use of macadam construction, a technique developed by Scottish engineer John Loudon McAdam. This method involved layering small, angular stones on a compacted subgrade, creating a hard, durable surface that resisted rutting and drained water efficiently.

Compared to the muddy, rutted tracks of earlier roads, macadam surfaces were revolutionary—they stayed passable in bad weather and required less maintenance. The National Road became one of the earliest large-scale applications of this method in America, showcasing how thoughtful engineering could quite literally pave the way to a stronger, more connected nation.

Even ambitious projects, like the Wheeling Suspension Bridge—once the longest suspension bridge in the world—highlighted how roads inspired innovation, connecting communities physically and symbolically. Dozens of the original stone bridges constructed along the National Road still stand today, silent but enduring monuments to 19th-century engineering. These graceful arches, many built from local limestone, carried generations of travelers across creeks and rivers and remain in use or preserved as historic landmarks—further proof of the road’s lasting legacy.

Boomtowns Born Overnight

Like magic, towns sprang up along the route, with the new road becoming the Main Street around which the towns were plotted. Taverns, inns, blacksmith shops, and general stores formed clusters that soon evolved from overnight stops into vibrant communities. Cities like Uniontown and Brownsville flourished as key staging points, while Wheeling, Washington, and Cumberland evolved into bustling hubs of industry and trade.

Columbus, Ohio, owes its very existence, and status as the state capital, to the Cumberland Road. Indianapolis was literally designed around it, its wide streets mapped specifically to accommodate the thoroughfare. Without this ambitious federal project, these cities—and many more—might never have existed at all.

The Fast Lane of Progress

The Cumberland Road not only shortened travel times, it rewired the nation’s economy and culture. Freight costs plunged, enabling farmers from Ohio and Indiana to compete in Eastern markets. This created the first truly national economy, as towns along the route saw new life from the constant flow of goods, money, and opportunity.

News and ideas also traveled faster than ever before. Newspapers once delayed by weeks now arrived fresh off the press, fueling national conversations and tying distant communities closer together. At the same time, the road became a major artery of migration. By the 1820s, nearly half of all settlers moving into the Midwest followed its path, drawn by the promise of land, freedom, and possibility.

All this movement brought more than money and mail. Traveling performers, politicians, preachers, and even circus troupes followed the same dusty road, turning frontier taverns into hotbeds of storytelling, song, and spirited debate. It wasn’t just commerce, but American culture itself, moving west, hitching a ride on wagon wheels.

Today’s Route—A Legacy You Still Drive

The Cumberland Road has never vanished entirely—it evolved as the country grew up. In 1926, it became U.S. Route 40, fondly called the “Main Street of America,” accommodating an ever-growing wave of automobile tourism. But transforming a 19th-century wagon route into a 20th-century motor highway required significant upgrades. Curves were straightened, grades were eased, and roadbeds were widened to accommodate cars and trucks. Many sections were paved over with concrete or asphalt, and modern culverts replaced aging stone bridges. Yet in many places, the bones of the original road remained intact, bearing witness to a century of evolving transportation needs and technology.

With the advent of the Interstate system in the 1950s, I-68 and I-70 closely shadowed the old alignment, often running mere yards from the original path carved through forests and mountains. If you happen to be cruising these interstate freeways, take notice those small-town exits and parallel service roads. Many still bear the proud signs “National Pike”—echoes of America’s first great highway.

Maybe Your Commute Isn’t So Bad?

Next time you’re tempted to grumble about a slight delay, take a breath and imagine wrestling a wooden wheel from deep, unyielding mud. Instead, sip your coffee, turn up your favorite playlist, and thank the generations who turned dirt paths into smooth highways. Tomorrow morning, you’re not just driving to work—you’re riding the backbone of a nation that refused to stay still.

Now that’s something worth thinking about on your morning drive.