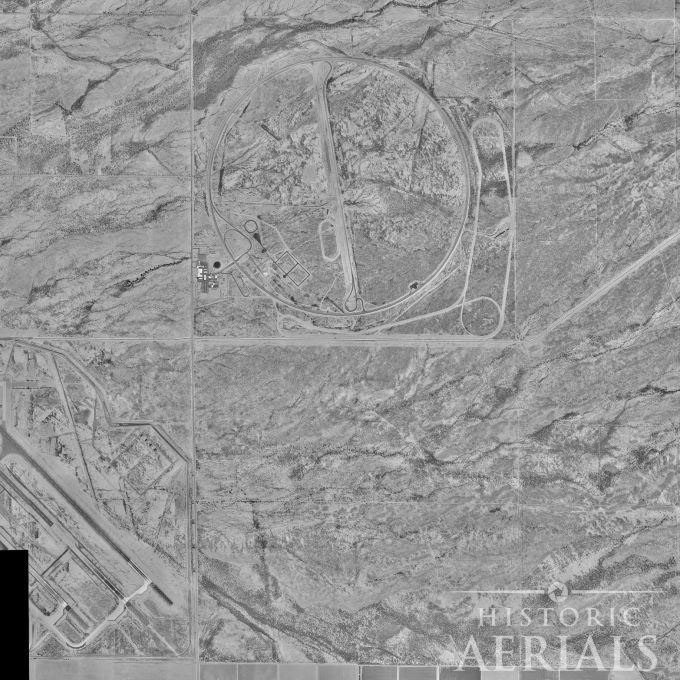

As a new resident of Arizona, I’ve spent some time scrolling through aerial imagery of the surrounding landscape, examining the evolution of cities like Phoenix, Tempe, and Mesa over the decades. This week, I spotted something I hadn’t seen before—a large circular track etched into the desert floor, flanked by smaller ovals, long narrow loops, and serpentine courses.

I’ve written about racetracks before—this was something different. The patterns were very specifically engineered, and not necessarily for speed. The newest imagery of the site showed its recent transformation into a planned suburban community, but the older aerials revealed a very intriguing past.

Some of you probably knew what it was right away. After a quick search, I learned that what I saw was the General Motors Desert Proving Ground. This was a massive facility where engineers tested cars against the desert’s extremes.

Of course, I knew that automotive testing happens all the time, of course, but I’d never really thought about where or how it was done until now. We all know the crash test dummies—those stoic icons of safety that we’ve seen in commercials and public safety advisories. But I bet that few people think about the places where entire fleets of vehicles are pushed to failure, rebuilt, and tested again.

These automotive proving grounds are highly secretive and surveilled, but aerial imagery gives us an idea of the variety and extent of testing that goes on. My discovery in Mesa sparked questions: when did automakers start building these secret kingdoms of speed and science? Where are the rest of them?

Here’s what I learned about automotive proving grounds and some of the most significant facilities:

In the earliest years of motoring, testing happened on public roads—dusty, uneven, and unpredictable. Engineers rattled through the countryside, jotting notes about failures and fixes. As cars grew faster and more complex, this method became unsustainable. Speed demanded safety, and safety demanded control. By the 1920s, the first dedicated proving grounds emerged, designed to simulate everything from cobblestone streets to mountain passes.

Milford: The Birth of the Modern Proving Ground

The pioneer was General Motors’ Milford Proving Ground, opened in 1924 in Michigan—their 100-year anniversary was celebrated last year. Spanning more than 4,000 acres, Milford became a living experiment in terrain and texture. There were steep grades, gravel pits, cobbled lanes, and rutted dirt tracks designed to replicate the harshest conditions. The centerpiece of this site is “’Black Lake’… a 67-acre test pad (equivalent to 51 football fields) used for dynamic vehicle testing in different weather conditions.”

Milford is where “cars go to find their breaking point.” Yet it wasn’t destruction for its own sake. It was refinement by fire. Over the decades, test drivers there endured Michigan’s bitter winters and humid summers to tune everything from Cadillac suspensions to Chevrolet truck frames.

Milford was also the site for the development of a wide variety of safety features. It hosted the first vehicle rollover tests in 1934, as well as the development of the first guardrails. GM also developed the “infant love seat” at Milford, which was used as a model for future child car seats.

Ford’s Dearborn Proving Ground: Testing at Home

A year after GM opened its Milford facility, Ford followed suit, opening the Dearborn Proving Ground in 1925 on the site of what had been southeast Michigan’s first airport. Built beside Henry Ford’s River Rouge industrial complex, it was symbolic: cars were born at the Rouge and tested next door. The oval track and endurance loops were modest by today’s standards, but revolutionary at the time. Engineers there went beyond just testing cars—they tested the public’s confidence in them.

Early Ford advertising proudly declared that its vehicles had “been tested on the Ford track,” a reassurance to buyers still wary of mechanical breakdowns on America’s rough, unpaved roads. Engineers pushed the Model T and its successors to failure points to improve reliability. One often-repeated anecdote describes engineers driving nonstop for 10,000 miles around the oval, pausing only for fuel and tire changes. This was a feat of endurance for both man and machine.

As vehicles evolved, Dearborn’s space grew cramped. By the 1950s, Ford had built their Arizona Proving Ground near Yucca, expanding into harsher climates. Still, Dearborn’s track remained the birthplace of Ford’s reputation for durability, where even the smallest squeak or rattle was treated like a personal insult.

Studebaker’s Bendix Woods: Innovation Among the Trees

While Detroit’s giants carved proving grounds into Michigan’s countryside, Studebaker ventured south into Indiana. In 1926, the company built its Studebaker Proving Ground at Bendix Woods near New Carlisle—a site that blended engineering with a surprising touch of artistry. In aerial imagery, you can still spot the vast pine plantation that spells out “STUDEBAKER,” a living billboard visible from the sky.

The proving ground itself was a marvel. It featured a high-banked oval, a network of handling roads, and specialized surfaces for suspension testing. Engineers here pioneered features that would become industry standards: four-wheel hydraulic brakes, aerodynamic streamlining, and improved steering geometry.

After Studebaker’s decline, the site transitioned into Bendix Woods County Park. Though the company is long gone, traces of the track remain—curved scars in the earth, reminders of when innovation was literally written into the landscape.

Packard’s Proving Grounds: Where Luxury Was Tested

If Studebaker’s proving ground was a blend of function and poetry, Packard’s was pure elegance. Opened in 1928 in Utica, Michigan, the Packard Proving Grounds served a company that saw testing not just as science but as performance art. The track’s buildings were designed by Albert Kahn, whose architectural precision matched Packard’s engineering ideals.

The high-speed oval and endurance courses were where Packard engineers fine-tuned the quietness of their luxury sedans. One internal memo from the 1930s described the goal: “At 70 miles per hour, one should hear nothing but the hum of progress.” Packard’s attention to testing helped establish Detroit as the epicenter of automotive craftsmanship.

The proving ground’s hangar-like garage still stands today, restored as part of a living museum where visitors can walk the same ground once thundered by the Packard Twelve.

Chrysler’s Chelsea Proving Grounds: The Age of Data

By mid-century, automotive engineering had entered a new phase—one defined by horsepower, complexity, and data. Chrysler responded with scale. In 1954, it opened the Chelsea Proving Grounds west of Ann Arbor, Michigan. Encompassing more than 3,800 acres, Chelsea featured a 4.7-mile high-speed oval, extensive durability roads, and specialized surfaces for noise, vibration, and harshness testing.

The facility quickly earned a reputation as both brutal and brilliant. Drivers spent hours pounding over Belgian block cobblestones designed to shake loose any weakness. The “Brake Hill” became legendary—its steep descent notorious for pushing prototypes to the brink. Engineers collected data obsessively, pioneering early telemetry systems that transmitted real-time readings from vehicles to control rooms.

A former test driver once joked, “You don’t drive here for fun; you drive here so someone else can.” That mix of courage and tedium defined the profession. Test drivers became translators between machine and engineer, articulating sensations—“a buzz in the steering column,” “a flutter near 60 mph”—that no computer could yet quantify.

GM’s Desert Proving Ground: Testing Under the Sun

And then there was the desert. In 1953, GM chose Mesa, Arizona, for its Desert Proving Ground, seeking the heat, dust, and sunlight that Michigan could never offer. The circle in the sand that first sparked my curiosity.

Spanning 5,000 acres, the site featured everything from an 11.6-mile oval to mountainous test loops with brutal inclines. Here, vehicles were tortured by the elements—metal expanding in the heat, paint fading in days, plastics cracking before lunchtime.

One story recounts a prototype pickup that caught fire mid-test when its undercarriage heat shielding failed. Instead of halting the test, engineers used the opportunity to design a more heat-resistant system. In these kinds of places, failure is always a part of the plan. The desert didn’t forgive, and that was the point.

For more than half a century, Mesa shaped GM’s vehicles in ways most consumers never knew. From Corvettes to Silverados, countless models endured the desert’s trial by fire. When GM closed the facility in 2009, relocating operations to Yuma, the land was redeveloped into the Eastmark community. Today, families walk dogs and push strollers over ground once rumbling with prototypes—another example of how landscapes evolve.

What’s Happening Now

The proving grounds are evolving just as rapidly as the cars being tested. These days, automakers are using them to refine electric drivetrains, calibrate autonomous systems, and stress-test advanced materials in extreme conditions. The once‑secretive ovals and skid pads have become research ecosystems for connected and sustainable transportation.

At GM’s Milford Proving Ground, teams now test electric vehicles alongside internal combustion models. Massive amounts of sensor data are collected to improve battery performance, regenerative braking, and real‑world range. The site’s expanded test corridors simulate both urban congestion and high‑speed highway automation, allowing continuous development of semi‑autonomous systems like Super Cruise and the next‑generation Ultra Cruise.

Ford’s Dearborn facility has been retooled for EV and battery validation, while Chrysler’s Chelsea Proving Grounds now houses wind and sound tunnels that help optimize efficiency for electric Jeeps and Ram trucks. Across these facilities, test drivers share the space with engineers specializing in machine learning, cybersecurity, and vehicle‑to‑infrastructure communication.

The industry’s shift toward sustainability is also visible on the ground itself—solar fields, recycled water systems, and low‑emission test vehicles increasingly define these campuses.

Why This Matters

Proving grounds might seem esoteric—a curiosity hidden behind fences. But they reveal how deeply the automotive industry shaped American identity. These sites are monuments to curiosity and persistence, places where imagination met asphalt. From Packard’s quiet luxury to Chrysler’s data-driven brutality, they chart the evolution of how we build, test, and trust machines.

Studying them through aerial imagery offers a rare perspective. You see geometry where others see dirt, design where others see decay. It’s a reminder that progress often leaves visible footprints—loops and ovals that tell stories of endurance, innovation, and human ingenuity.

And as I look again at that perfect circle in the Arizona desert, I think of the engineers and drivers who spent their days chasing perfection under the sun. They didn’t make headlines or win trophies, but they built the unseen backbone of modern mobility. Every curve they tested still echoes on the roads we drive today.