So you’ve found the perfect waterfront property and you’re already imagining the dock you’ll build, the backyard barbecues, the early‑morning kayak trips, and the long, quiet evenings by the water.

Slow down there, captain. Before you fall in love with the view, ask a less romantic question: how long will the land under that view stay where it is?

Waterfront property sits where water, land, and law intersect. Water shifts. Land changes shape. Law tries—sometimes awkwardly—to track those changes. If you’re thinking about buying waterfront property, or trying to understand water boundary laws before signing anything, you’re already ahead of most buyers.

This article distills the essentials: how different kinds of waterfronts behave, why boundaries aren’t as fixed as they look, and how tools like historical aerial imagery help you see decades of change at a glance.

Why Waterfront Property Isn’t Just “Regular Land With a View”

Most land stays put; however, waterfront land behaves differently. Rivers migrate. Lakes rise and fall. Bluffs erode. Beaches widen and shrink. The shoreline you see during a showing may not be the shoreline you’ll inherit years later.

Three slow‑change concepts shape most water boundary laws:

- Accretion: land that slowly builds as sediment collects.

- Reliction: land exposed when water slowly recedes.

- Erosion: land gradually lost as water wears it away.

When these changes happen gradually and naturally, the legal boundary often moves with the water. Your lot can expand, contract, or shift shape, and those changes can be legally meaningful.

One exception matters: avulsion, a sudden change (a flood, a channel jump, a bluff collapse). In many states, the legal boundary stays where it was before the event, even if the physical shoreline jumps.

What Kind of Waterfront Are You Dealing With?

“Waterfront” covers several very different environments, each with its own rules about what you own and what you’re allowed to build. Before you start planning docks, decks, or shoreline improvements, you need to know which category your waterbody falls into.

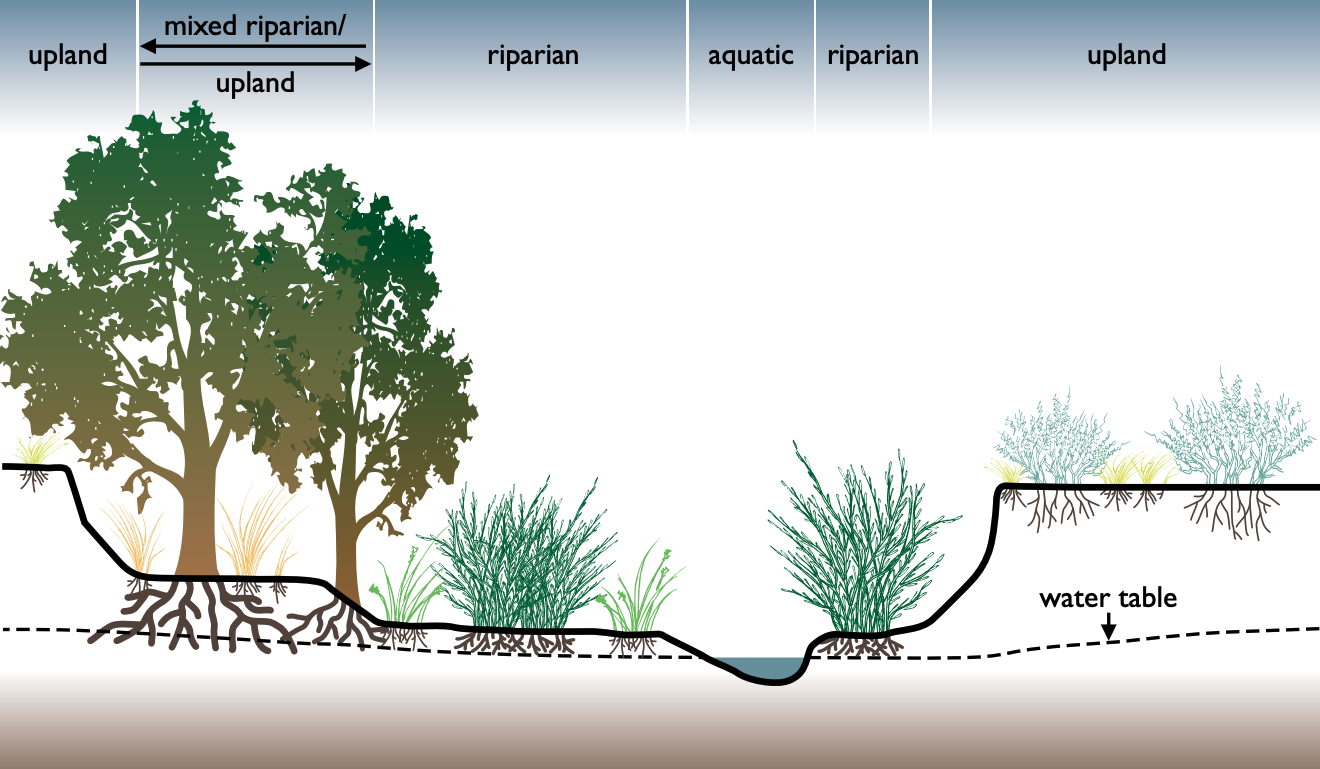

Riparian: Rivers and Streams

Rivers shift gradually over time, and as a result, their boundaries rarely remain fixed. Outside bends erode, inside bends accumulate sediment, and secondary channels appear or disappear. A home comfortably set back from the bank decades ago may now sit much closer.

Legally, many riparian owners hold title to the center of the active channel (the “thread” of the stream) or to a gradient boundary defined by state law.

What owners typically want to know:

- You usually own to the middle of the flowing channel, not the whole width.

- Docks, ramps, and bank stabilization usually require permits, even if they sit in front of your property.

- If the riverbank moves slowly over time, the ownership line often moves with it.

- If the river suddenly jumps course (avulsion), the legal boundary may remain fixed at its prior location.

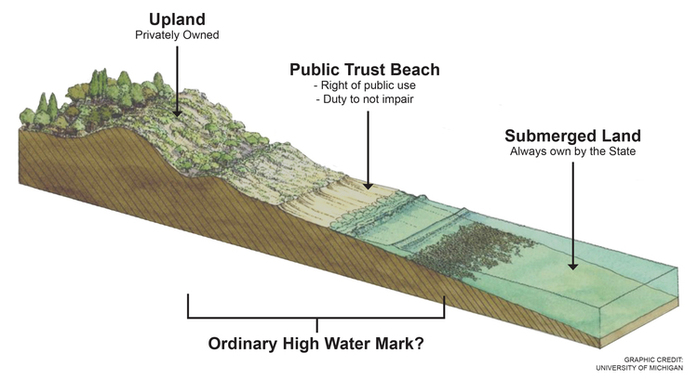

Littoral: Lakes and Ponds

Lakes look calm; nevertheless, their shorelines shift over decades due to drought cycles, dam management, storms, and wave action. Long-term imagery often shows noticeable change.

Boundaries here are often tied to an ordinary high-water mark (OHWM) or a fixed elevation rather than the exact waterline on the day of your visit.

What owners typically want to know:

- You may own the upland, while the lakebed itself is commonly state-owned.

- Docks and piers usually require state or local permits, and you must stay within your projected shoreline frontage.

- Land newly exposed during low water may become yours through reliction, though regulations may still govern its use.

- When water levels rise again, that “extra land” can quickly disappear.

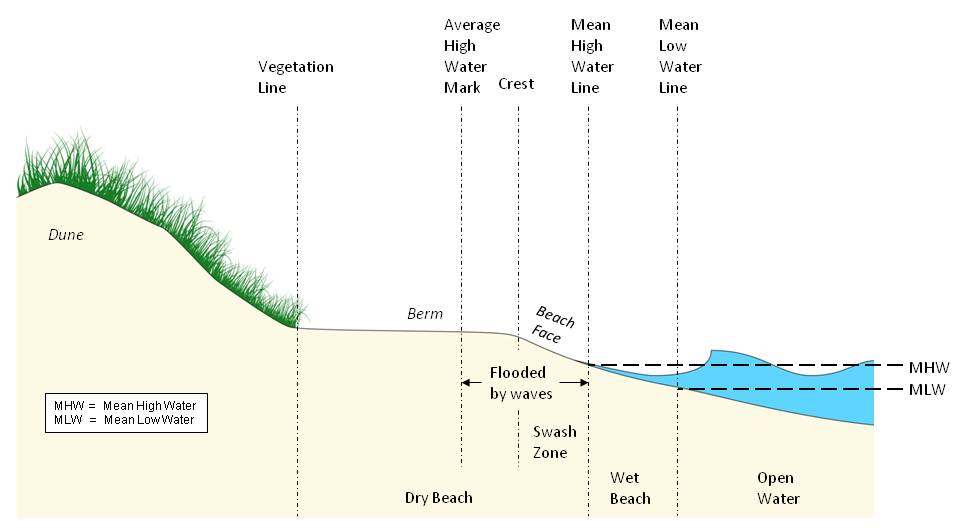

Tidal Littoral: Coasts and Bays

Tides, waves, storm surges, and long-term sea-level rise reshape coastlines continuously, and consequently, ownership near the shore can come with added complexity. Because water moves on predictable cycles, coastal boundaries often use the mean high-water line (MHWL)—a long-term average of high tides.

Above that line, you may have private ownership. Below it, the seabed is often held by the state under public trust doctrine.

What owners typically want to know:

- You often own only the dry sand or upland above the MHWL.

- Any structure built seaward—piers, docks, seawalls—nearly always requires multiple permits, sometimes including federal approval.

- Beach width can vary drastically, but private ownership does not automatically expand when sand temporarily accumulates.

- Hard armoring (seawalls, revetments) is heavily regulated and sometimes restricted.

Knowing exactly which category you’re dealing with determines how far your ownership extends, what improvements are allowed, and which agencies must sign off before work begins. It’s the foundation for reading deed language correctly and understanding what the shoreline might look like decades from now.

Other Practical Questions Every Waterfront Buyer Should Ask

Do I actually have legal access to the water?

Owning land near water is not the same as owning land to the water. In many communities, buyers assume they can reach the shoreline simply because it’s visible from the property. But unless your deed explicitly includes waterfront footage or grants an easement, your “waterfront” may be nothing more than a view. Before buying, confirm whether access is private, shared, or nonexistent. A title search should reveal easements for paths, docks, or community access points—if they exist at all.

How far out can I build a dock or pier?

Even when you own true waterfront footage, the water itself may not belong to you. Rivers, lakes, and tidal areas often involve submerged lands owned by the state and regulated under public trust doctrines. That means docks, piers, lifts, or ramps almost always require permits—sometimes from multiple layers of government. Federal agencies (such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers), state environmental departments, county planners, and local zoning boards may all have a say. Buyers should treat dock construction as a regulated activity, not an automatic right.

Are there buffer zones or setback requirements?

Properties within a certain distance of wetlands, lakes, rivers, or tidal waters often fall under environmental buffer rules. These can restrict clearing vegetation, altering slopes, or enlarging existing structures. Some states impose 50-, 100-, or even 1,000-foot review zones where shoreline changes trigger additional scrutiny. If you’re planning a new build or a teardown-and-rebuild, you need to know whether the site falls within these zones.

Will I need flood insurance—and how much will it cost?

Standard homeowners insurance rarely covers flood damage, and many policies exclude any form of land movement, including erosion. Buyers should request the seller’s elevation certificate (if one exists) and contact an insurance professional to get realistic numbers. If you’re using a mortgage, lenders may require flood insurance based on federal flood maps. Premiums can vary dramatically depending on elevation, recent claims, and new FEMA map updates.

With these bigger-picture issues in mind, the rest of the article—legal boundaries, imagery analysis, and long-term management—makes far more sense. how far your ownership extends, what improvements are allowed, and which agencies must sign off before work begins. It’s the foundation for reading deed language correctly and understanding what the shoreline might look like decades from now.

Real‑World Warnings: Two Places That Make the Risks Clear

Simonton, Texas: A River That Shifted Back to Its Old Path

The Brazos River west of Houston follows looping bends that change shape over time. For decades, homeowners in Simonton enjoyed wide backyards along one of these bends. After major storms, a few feet of bank would disappear—annoying, but expected.

Then the pace increased. Yards vanished. Fences collapsed. Some decks ended up hanging over the water. Eventually the river reached the street itself, and residents warned visitors not to trust GPS because the “road” was now open water.

Historic aerials show that the subdivision sits directly within the river’s historical migration belt. Old oxbows and abandoned channels reveal the Brazos had occupied this ground before. The landscape never was as stable as the lot lines implied.

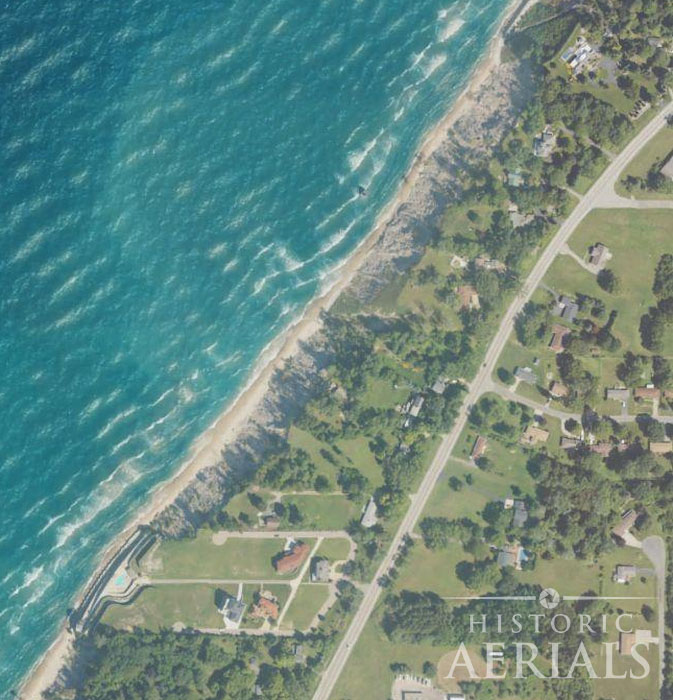

St. Joseph, Michigan: Bluffs That Look Permanent Until They Aren’t

Along Lake Michigan near St. Joseph, homes perch on steep bluffs that feel immovable from ground level. But historical imagery tells a different story. Property owners on the lake’s shoreline have been at war with coastal erosion for decades. In the 1950s, the high bluffs stood noticeably farther from the lake. But storms and high‑water cycles have continued carving the shore inward relentlessly.

During the late 2010s, some locations lost dozens of feet of bluff in just a few seasons. Stairways dangled. Patios fractured. Michigan now designates large stretches here as High‑Risk Erosion Areas requiring wider setbacks and special permits.

A side‑by‑side of 1950s and modern aerials makes the pattern unmistakable.

How Water Boundary Laws Decide “Who Owns What”

When water shifts, the key legal question is straightforward: who owns the newly exposed or newly submerged land?

General principles:

- Gradual natural change (accretion, reliction, erosion): boundary moves with the water.

- Sudden, dramatic change (avulsion): boundary usually stays put.

- Artificial change (fill, dredging): often treated differently than natural shifts.

If sediment gradually builds along your shoreline due to natural forces—even if a far‑upstream dam influences the flow—you often gain that land. But adding dirt to create new land generally doesn’t expand ownership.

These distinctions matter, and they hinge heavily on good documentation.

Deeds, Surveys, and the Fine Print

Vague deed language causes real problems. Terms like:

- “the water’s edge”

- “the meander line”

- “the thread of the stream”

may not match the current physical shoreline. As decades of change accumulate, poorly defined boundaries become disputes.

A clear survey anchors the boundary to specific standards such as the gradient boundary of a river, the ordinary high‑water mark of a lake, or the mean high‑water line of a coast. It also documents visible evidence of accretion, reliction, and erosion.

Without this clarity, it’s easy to end up with:

- a dock partly on someone else’s land,

- a seawall built on public trust land, or

- a house too close to a bluff edge under today’s rules.

Using Historical Aerials to Understand Risk

Historical aerial imagery is one of the most effective tools for evaluating waterfront property. With decades of consistent imagery, you can see:

- whether a riverbend has migrated steadily,

- whether a bluff is retreating,

- how a beach or delta has grown or shrunk,

- where old roads, docks, or lots once existed.

The method is simple:

- Start with a current aerial of the property.

- Scroll backward through time.

- Compare the shoreline to fixed reference points: roads, houses, tree lines.

- Look for long‑term direction and pace—not one‑year anomalies.

- Cross‑check with old topographic maps or subdivision plats.

This turns guesswork into a visual timeline: “The shoreline has moved X feet in Y years.”

The Human Layer: Engineering, Regulation, and Insurance

Water isn’t the only factor shaping waterfront risk.

Engineering: Seawalls, bulkheads, riprap, levees, and drainage projects alter currents and sediment transport. They can stabilize one site while increasing erosion nearby and typically require significant permitting.

Regulation: Many states and municipalities map erosion‑hazard zones, enforce shoreline setbacks, and restrict new armoring. A structure legally built decades ago may not be rebuildable today.

Insurance: Standard homeowners policies often exclude floods and land movement. Flood insurance may cover inundation but not bluff retreat. If insurers or lenders decide a parcel is high‑risk, property value and financing options can shrink.

Managing Risk Without Losing the Joy

Waterfront living can be wonderful—and safe—when you make informed decisions.

If you already own waterfront property, start with documentation:

- photos of the shoreline or bluff edge,

- copies of old aerials,

- surveys, permits, and insurance documents.

Then ask:

- Has the shoreline moved during my ownership?

- Do old images show a consistent trend?

- Are there visible warning signs like cracks or slumps?

- Do my deed and survey match real‑world conditions?

If you’re considering buying, slow down just enough to:

- review decades of imagery,

- obtain a current survey,

- understand local setbacks and hazard zones,

- talk to a surveyor, an attorney, and—if needed—an engineer.

Some parcels will pass every check. Others will reveal significant long‑term risks. The value of due diligence is knowing which is which.

The Bottom Line: Water Writes in Pencil

Waterfront property will always be appealing. The view is real. The risks are, too.

Water boundary laws, historical imagery, erosion maps, and expert guidance don’t exist to discourage ownership—they help you understand the long arc of change shaping the shoreline.

Water writes in pencil. Your decisions don’t have to. With the right information, you can choose where to buy, where to build, and how to protect your investment—confident that you’ve seen the full story before you sign.