Aerial photography did not begin with airplanes or satellites. It began with a technical problem that early photographers could not yet solve: how to make a clear, reliable photograph from a moving platform. For the first two decades of photography, the answer was simple and unsatisfying—you couldn’t. The cameras were slow, the chemistry was fragile, and even small amounts of motion were enough to ruin an image.

That limitation mattered. Long before powered flight, humans were already rising into the air in hot‑air balloons, gaining perspectives no one had ever seen before. But photography lagged behind flight. Early photographic processes were designed for stillness: controlled studios, fixed architecture, carefully posed subjects. The sky was simply too unstable for the technology of the time.

Everything changed in 1851 with the introduction of the wet plate collodion process. This new method dramatically shortened exposure times, produced exceptionally sharp negatives, and—crucially—forced photographers to become mobile by necessity. By requiring plates to be exposed and developed while still wet, the process pushed photography out of the studio and into the field. In doing so, it laid the technical foundation that would make the first aerial photographs possible.

Photography Before Wet Plate Collodion

To understand why wet plate collodion was such a turning point, it helps to look at what photographers were working with before it arrived. Early photographic processes could produce stunning images, but they imposed strict limits on where and how photographs could be made.

Introduced in 1839, the daguerreotype was the first widely adopted photographic process. It produced a direct positive image on a silver‑coated copper plate, capable of extraordinary detail and tonal range. Each plate was sensitized with chemical vapors, exposed in the camera, then developed and fixed using a hazardous and highly controlled workflow.

Daguerreotypes were visually impressive, but they were also unforgiving. Exposure times in the early years could stretch into minutes, making motion blur unavoidable. The finished image was a one‑of‑a‑kind object—there was no negative, and no way to reproduce it.

These limitations effectively anchored photography in place. Long exposures demanded still subjects. Complex chemical handling favored indoor or semi‑controlled environments. Even when photographers ventured outdoors, they worked with scenes that could tolerate patience and stability.

This made early photography incompatible with flight. Balloons drift, rotate, and vibrate. Asking a daguerreotype plate to remain sharp under those conditions was unrealistic. The problem was not imagination or courage—it was physics and chemistry.

The Invention of the Wet Plate Collodion Process

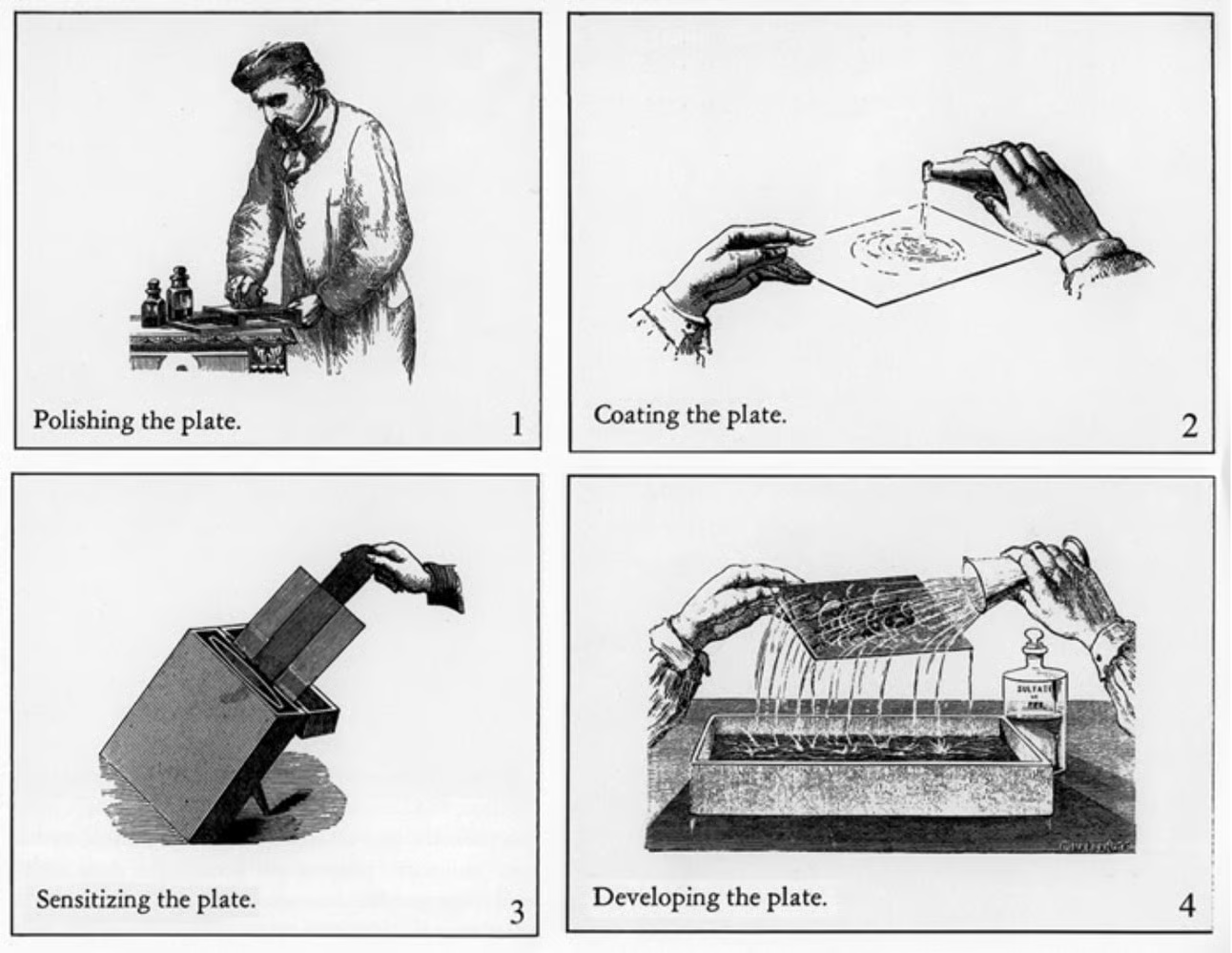

In 1851, English sculptor and amateur photographer Frederick Scott Archer published a new photographic method that quietly redefined the medium. Known as the wet plate collodion process, it combined the sharpness of metal‑based photography with the flexibility and reproducibility that earlier techniques lacked.

Archer’s process replaced expensive silver‑coated plates with glass negatives. By coating a glass plate in collodion and sensitizing it in silver nitrate, photographers could create a highly detailed negative at a fraction of the cost of a daguerreotype. Archer never patented the process, and it spread rapidly through photographic circles on both sides of the Atlantic.

Wet plate collodion required precision and speed. A glass plate was coated with collodion, immersed in a silver nitrate bath, and placed into the camera while still wet. After exposure—often just a few seconds in good light—the plate had to be developed immediately, before the collodion dried.

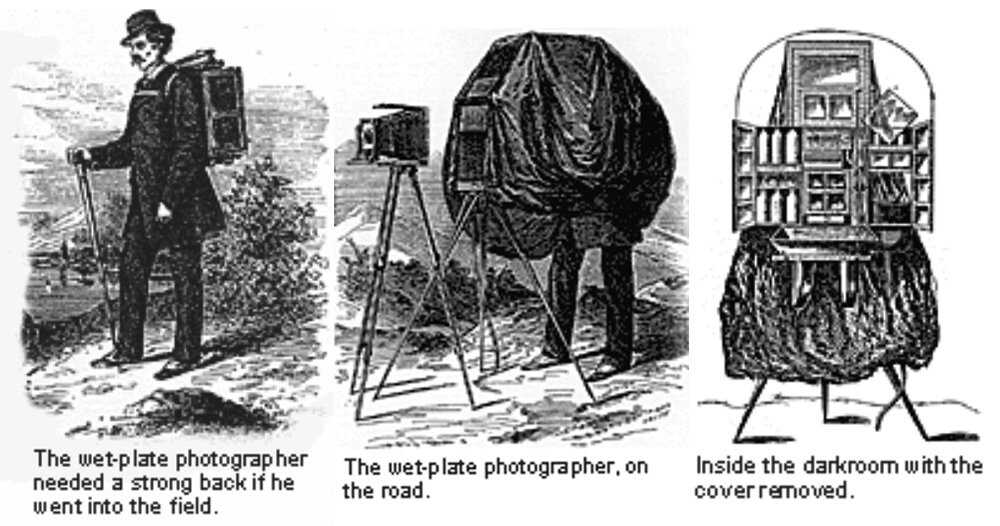

This meant photographers had to carry their entire darkroom with them. Wagons, tents, and portable boxes became standard equipment. The process was demanding, but it rewarded careful technique with images of remarkable clarity.

Why Wet Plate Collodion Changed Photography

Wet plate collodion did more than improve image quality. It reshaped the daily practice of photography and expanded what photographers believed was possible.

Compared to earlier processes, wet plate collodion dramatically reduced exposure times. While it still required careful handling, it allowed photographers to capture scenes that included subtle movement and finer detail without sacrificing sharpness.

Because the image existed as a negative on glass, photographers could produce multiple prints from a single exposure. This transformed photography from a collection of unique artifacts into a medium capable of documentation, comparison, and distribution.

Perhaps most importantly, wet plate collodion normalized the idea of photography as a field activity. Photographers became accustomed to working under time pressure, managing chemistry outdoors, and adapting to unpredictable environments. These habits would prove essential when photography left the ground.

Why Aerial Photography Was Impossible Before Wet Plate Collodion

The desire to photograph the world from above existed long before the technology allowed it. What held photographers back was not the lack of flying machines, but the limitations of photographic chemistry.

Early photographic processes required exposures far too long to tolerate the constant movement of a balloon. Even small shifts in position would blur an image beyond recognition.

Daguerreotypes were especially ill‑suited to aerial work. Their long exposure times, lack of reproducibility, and delicate handling requirements made them incompatible with the unstable conditions of flight.

Early Human Flight and the Hot Air Balloon

Before airplanes, balloons offered the only practical means of sustained human flight. They could lift observers, instruments, and—eventually—photographic equipment to heights that revealed entirely new perspectives.

Hot‑air balloons provided relatively smooth ascents and enough space to carry cameras and supplies. For photographers, they represented the first realistic opportunity to attempt aerial images.

Balloons drifted with the wind and rotated unpredictably. Managing exposure, focus, and chemical timing under these conditions required exceptional preparation and patience.

The First Experiments in Aerial Photography

Once wet plate collodion made shorter exposures and portable workflows possible, photographers began experimenting with photography from the air.

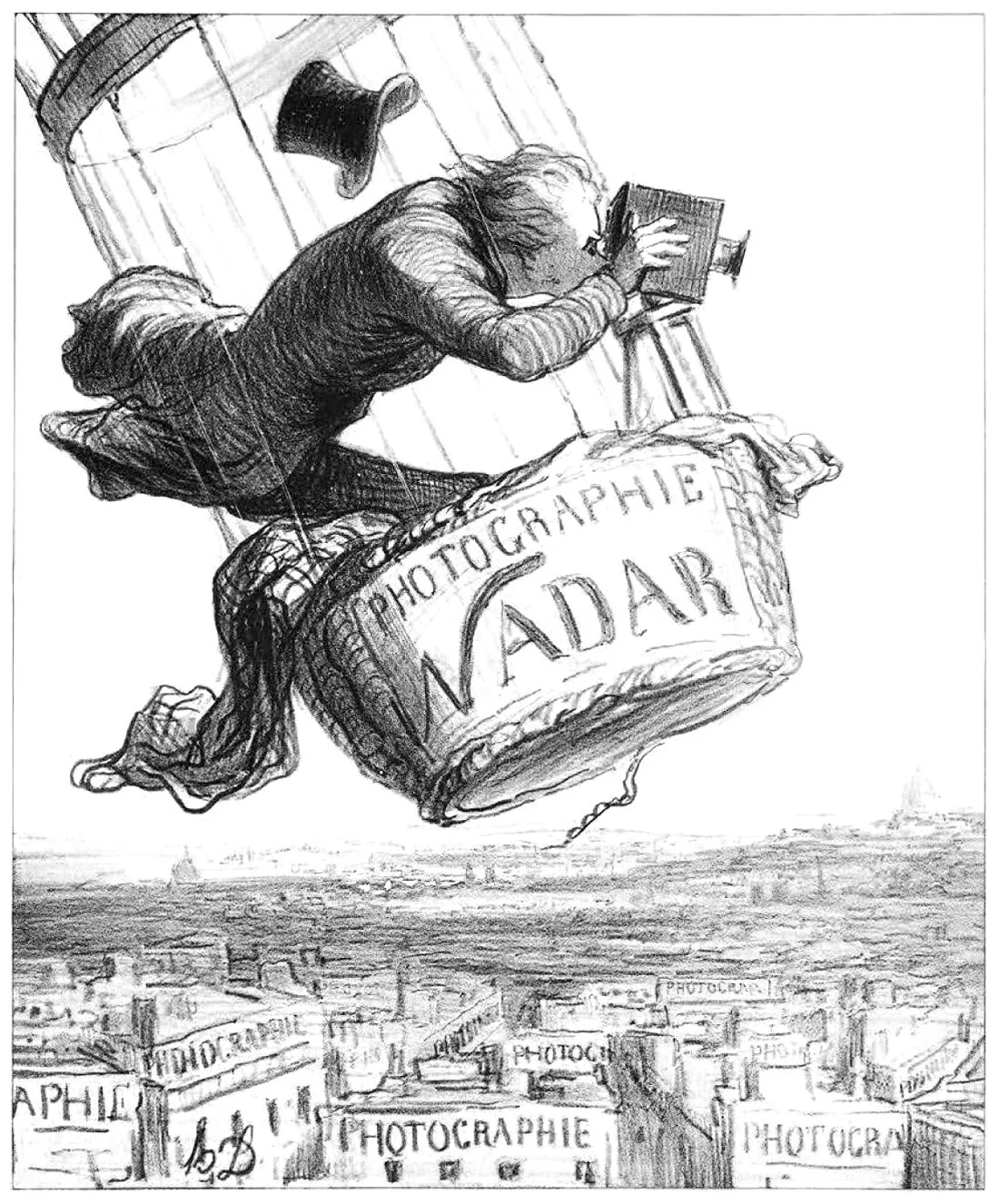

In 1858, French photographer and aeronautical enthusiast Nadar ascended in a hot‑air balloon over the outskirts of Paris and produced what is widely regarded as the first aerial photograph. Although the image itself no longer survives, contemporary accounts confirm the attempt and its success.

Nadar proved that photography could function in the air. His work demonstrated that wet plate collodion could be prepared, exposed, and developed under the constraints of flight.

James Wallace Black and the Oldest Surviving Aerial Photograph

Two years later, aerial photography produced its most enduring early image.

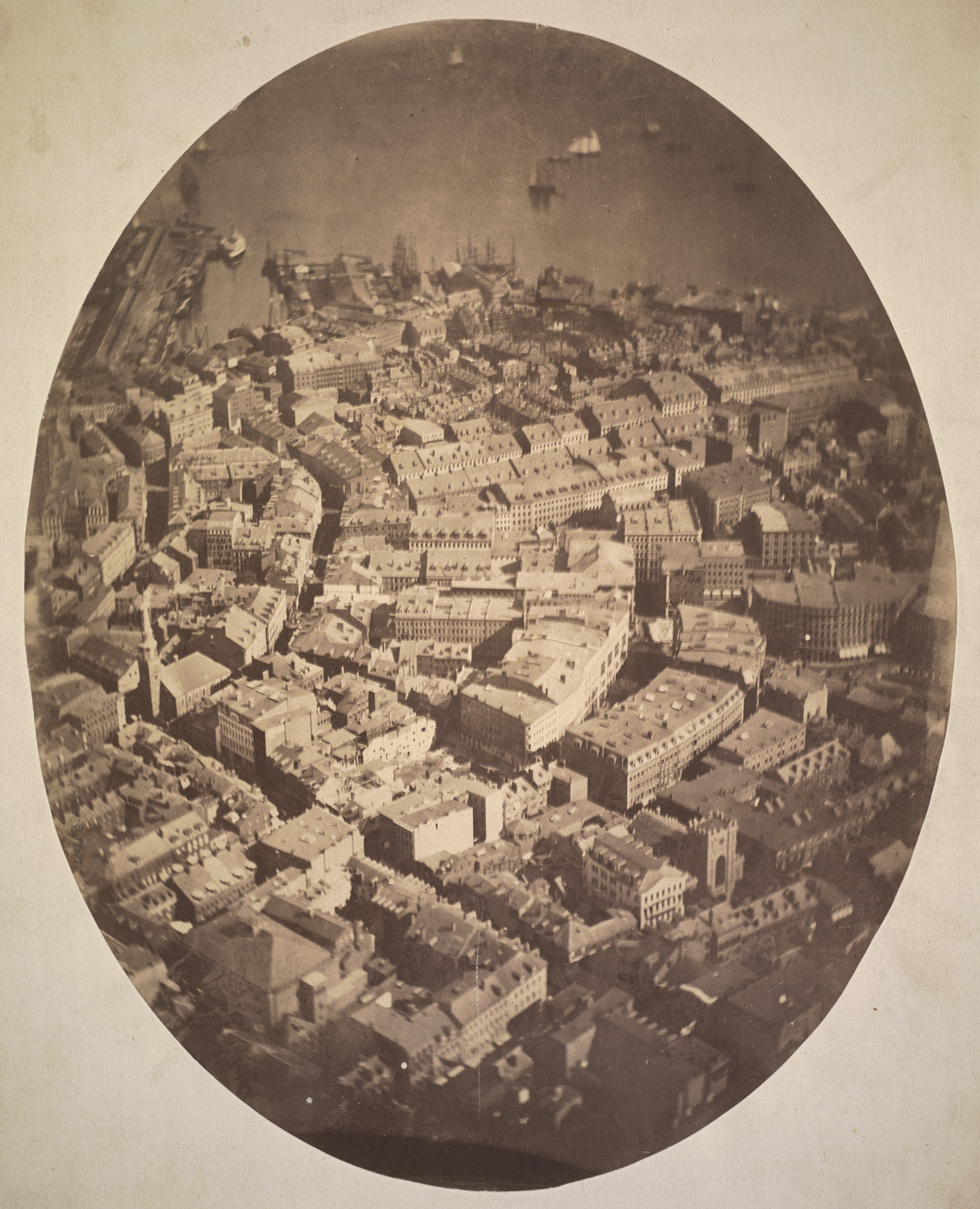

In 1860, photographer James Wallace Black, accompanied by balloonist Samuel Archer King, captured an aerial view of Boston from a hot‑air balloon. The resulting image is widely recognized as the oldest surviving aerial photograph.

Black’s success depended entirely on wet plate collodion. The process provided the exposure speed, image clarity, and portability required to produce a usable photograph from a moving platform.

How Wet Plate Collodion Shaped the Future of Aerial Photography

The technical lessons learned during these early experiments carried forward. Later innovations—dry plates, roll film, stabilized cameras, and eventually aircraft‑based photography—built directly on the foundation wet plate collodion established.

As photographic materials improved, aerial photography became more reliable and widespread. But the core challenge—capturing sharp images from unstable platforms—was first solved in the wet plate era.

Why the Wet Plate Collodion Process Still Matters Today

Modern aerial imagery feels effortless by comparison, but it rests on a fragile chain of historical breakthroughs. Wet plate collodion was the catalyst that allowed photography to leave the ground. It transformed photography into a mobile, adaptable tool and made the first aerial perspectives possible.

Every aerial image taken since—whether from an airplane, drone, or satellite—traces its lineage back to that moment when chemistry, ambition, and altitude finally aligned.