Once you learn the shape, you can’t unsee it. A clean oval ghosting beneath cul-de-sacs, stitched into golf fairways, hiding behind warehouse rows. From above, the outline snaps into focus — the long oval where the rail once ran — the street encircling a park, the curved tree line at the edge of an empty field, or even a cemetery laid out in graceful, concentric rings.

Every spring, the sport’s living heartbeat still rumbles across three stages: two breathless minutes in Kentucky, a sharp turn through Baltimore, and the long, unforgiving stretch in New York. The Triple Crown is ritual and roll call — Derby, Preakness, Belmont — our national reminder that speed and nerve can still command a crowd. Yet the country’s racing story isn’t only told by packed grandstands. It’s also etched into the land and preserved in aerial imagery.

From Fairgrounds to National Shrines

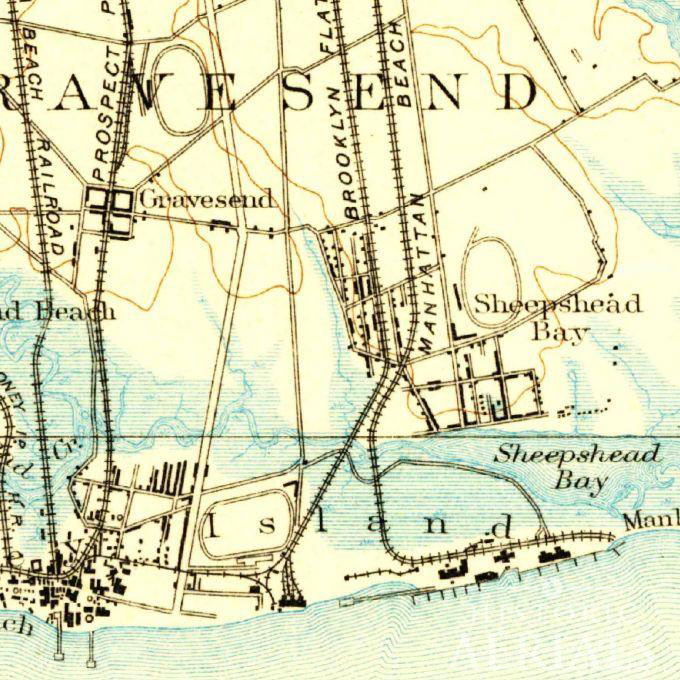

Horse racing has deep roots in America, dating back to colonial times. The first track appeared on Long Island in 1665. The bloodlines that defined American speed arrived in flesh and bone. In 1798, the English Derby winner Diomed came to Virginia. The supposedly washed-up stallion sired so many foals that many people now call him the father of American Thoroughbreds.

The Post-War Racing Boom

By the mid-19th century, racing no longer belonged only to Southern planters or city elites. It spread westward with the frontier. Illinois, Missouri, Texas, and Louisiana all staged organized meets by the 1840s. Many took place at county fairgrounds, where trotting races were as common as flat Thoroughbred contests.

The Civil War (1861–65) interrupted this growth. Racing virtually ceased in war‑torn areas. The famed breeding farms of Virginia and the Carolinas suffered heavy losses as armies requisitioned Thoroughbred horses for military service. Even so, racing rebounded quickly in the post‑war Reconstruction era.

The real watershed came in 1863 with the debut of Saratoga Race Course in upstate New York. For the first time, a purpose‑built track outside the big cities became a national destination. Within a decade, other giants followed. Jerome Park in the Bronx hosted the first Belmont Stakes in 1867. Pimlico opened in Baltimore in 1870. Churchill Downs introduced the Kentucky Derby in 1875. With New Orleans’ rebuilt Fair Grounds and New Jersey’s Monmouth Park joining the mix, the foundation of America’s racing calendar was set.

Brooklyn’s Pulse and the Gilded Age Expansion

If Saratoga and Kentucky gave racing its prestige, Brooklyn gave it its pulse. By the 1880s, the borough was home to Brighton Beach, Sheepshead Bay, and Gravesend — three tracks that turned Coney Island into racing’s capital. Summer afternoons drew thousands, with big‑money stakes that rivaled anything in England. At its peak, Brighton Beach reportedly ranked as Brooklyn’s single largest employer.

Meanwhile, Chicago, New Orleans, and San Francisco weren’t far behind. Each city boasted its own courses. By 1890, the country had more than 300 racetracks. They ranged from polished metropolitan ovals to makeshift fairground tracks in small towns. Racing had become America’s sport of the Gilded Age.

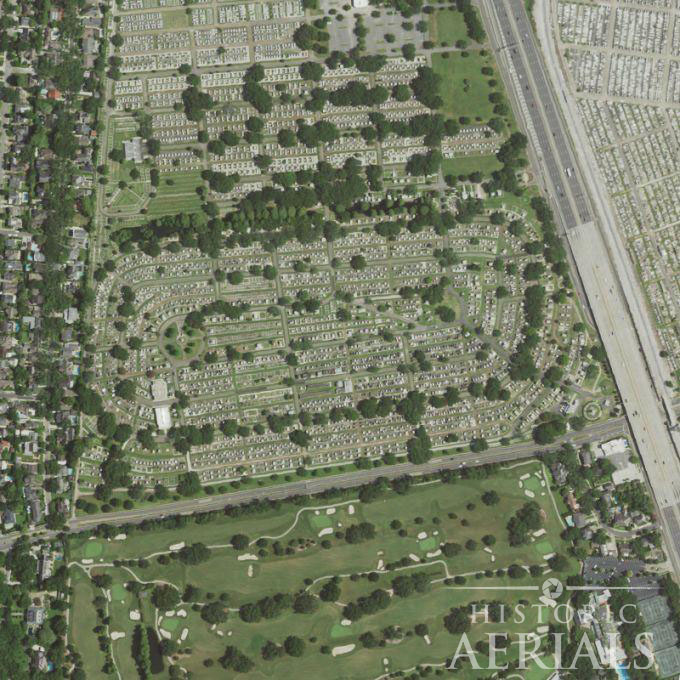

Even in New Orleans, the Metairie Race Course, a grand track known for its distinct oval layout, thrived. However, when the Metairie Jockey Club went bankrupt in 1872, a rival citizen named Charles Howard bought the land. Club members had once denied him membership. In a striking act of historical retribution, he transformed the track into Metairie Cemetery. The layout of the course, including the rail, still shapes the cemetery’s main avenues, a perfect ghost oval on the landscape.

Three Hundred Tracks and Counting

From hundreds of active courses, the U.S. shrank to just a couple dozen. Brooklyn’s three proud tracks never reopened. The Belmont Stakes wasn’t even run in 1911 and 1912. Owners shipped horses overseas, and the sport teetered on extinction.

What saved racing was a new way to bet. Kentucky tracks, led by Churchill Downs, introduced the pari-mutuel system in 1908. Instead of shady bookmakers, bets went into a transparent pool, with odds set by the public. Reformers tolerated it, governments could tax it, and racing finally had a lifeline. By 1913, New York cautiously reopened its tracks under stricter rules.

The Progressive-Era Crackdown

The next chapter took a darker turn. Reformers in the early 1900s saw the betting rings as symbols of corruption. Popularity bred backlash. States moved swiftly. New York outlawed bookmaking in 1908, and by 1911 every track in the state had shut down. California banned wagering in 1909. Illinois, New Jersey, and other states soon followed.

The result was devastating. From hundreds of active courses, the U.S. shrank to just a couple dozen. Brooklyn’s three proud tracks never reopened. The Belmont Stakes did not run in 1911 or 1912. Owners shipped horses overseas, and the sport teetered on extinction.

A New Way to Bet and a Roaring Comeback

What ultimately saved racing was a new way to bet. Kentucky tracks, led by Churchill Downs, introduced the pari‑mutuel system in 1908. Instead of shady bookmakers handling private odds, bets flowed into a transparent pool, with the public setting the prices. Reformers tolerated this system, governments could tax it, and racing finally gained a lifeline. By 1913, New York cautiously reopened its tracks under stricter rules.

After World War I, the sport came roaring back. Tracks no longer resembled the chaotic dens of the Gilded Age. Instead, owners tried to run them as orderly, respectable businesses. States desperate for revenue during the Depression leaned into it, and by the 1930s, racing was back in style.

The Depression-Era Building Boom

The building boom was dazzling. California stole the spotlight with Santa Anita Park in 1934 — an Art Deco palace at the foot of the San Gabriels — and Del Mar in 1937, “where the turf meets the surf.” On the East Coast, Boston gained Suffolk Downs, Rhode Island opened Narragansett Park, and Delaware built its namesake oval. Kentucky added Keeneland in 1936, created by horsemen who wanted a track devoted to tradition rather than spectacle.

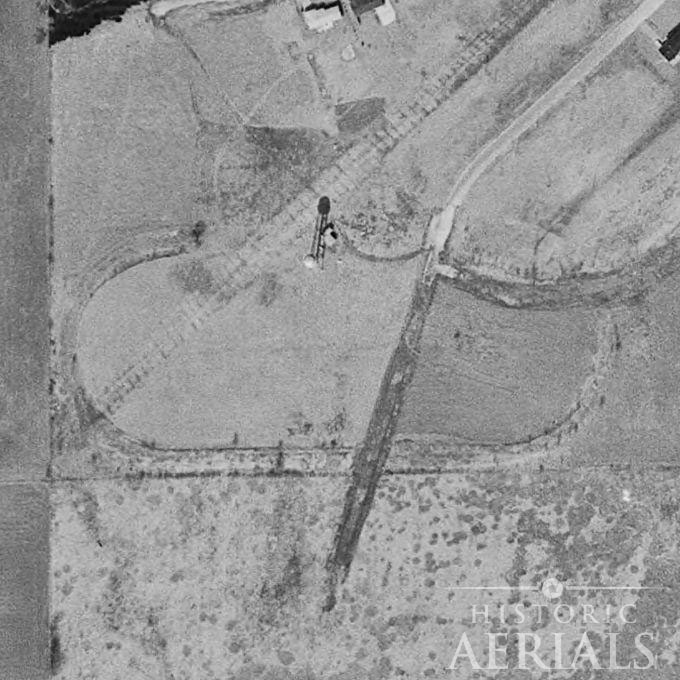

Even in the Midwest, where racing had nearly vanished, new venues rose. Arlington Park near Chicago flourished. Nebraska’s Ak‑Sar‑Ben opened to full houses. Garden State Park in New Jersey launched in 1942. By the late 1930s, racing had become mainstream entertainment, second only to baseball in the nation’s affections. In fast‑growing cities like Houston, tracks such as Epsom Downs joined this wave, purpose‑built for regulated pari‑mutuel wagering and designed to operate as orderly, revenue‑generating businesses — a footprint you can still trace today in historic aerial imagery.

Even in the Midwest, where racing had nearly vanished, new venues rose. Arlington Park near Chicago flourished. Nebraska’s Ak‑Sar‑Ben opened to full houses. Garden State Park in New Jersey launched in 1942. By the late 1930s, racing had become mainstream entertainment, second only to baseball in the nation’s affections.

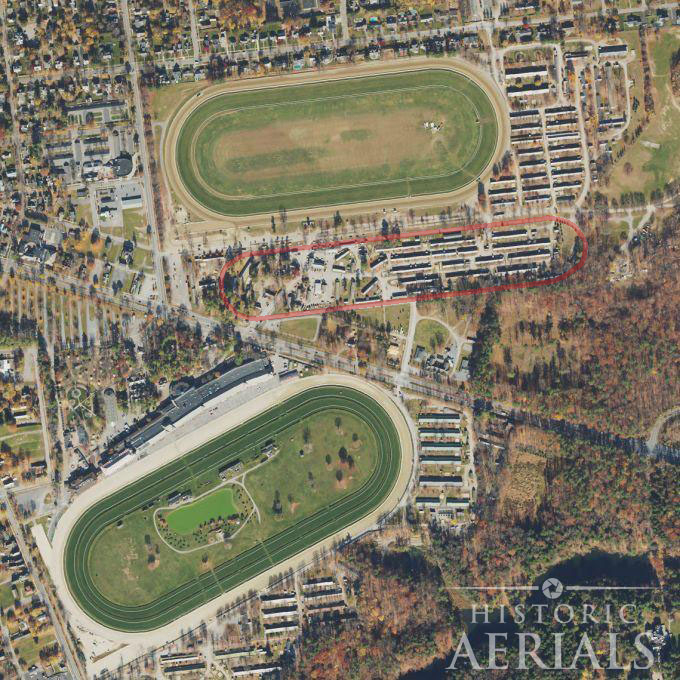

Harness Lights and Quarter Miles

While the Thoroughbreds reclaimed the headlines, other forms of racing carved out their own niches. Harness racing, once confined to daytime fairgrounds, exploded after World War II thanks to new technology. Roosevelt Raceway on Long Island pioneered night racing under floodlights in the 1940s, and its mobile starting gate kept races smooth and fair.

While Roosevelt trailblazed this new era, other tracks reached even deeper into the past. Freehold Raceway in New Jersey is the oldest continuously operating racetrack in the United States, with races dating back to the 1830s. Goshen Historic Track in New York, founded in 1838, now holds National Historic Landmark status.

Quarter Horse racing, long the province of ranch‑country match sprints, finally gained formal venues in the 1940s. Tucson’s Rillito Park opened in 1943 with a straight chute built for sprinters, a feature that other tracks soon copied. By 1951, California’s Los Alamitos had joined the circuit, laying the foundation for quarter horses as a major branch of the sport.

Across the Midwest, states like Ohio, Illinois, Nebraska, and Minnesota all established tracks during the 1930s. For example, Ak‑Sar‑Ben in Omaha ran its first full meet in 1935 after Nebraska approved pari‑mutuel wagering. By the end of the decade, racing once again operated as a nationwide industry and an important source of tax revenue for many states.

War and Renewal

World War II briefly dimmed the lights again. In 1945, the federal government suspended racing to save fuel. Santa Anita and other West Coast tracks closed altogether during the war. Santa Anita even served as an internment center for Japanese Americans. Yet the return came quickly. That June, the Kentucky Derby resumed, and pent‑up demand made the postwar years some of the sport’s most profitable.

Tracks old and new flourished. Monmouth Park reopened in 1946 after half a century of silence. Florida’s Gulfstream Park, opened just before the war, became a winter staple. Attendance records fell year after year. Network radio — and soon television — brought the big races into homes nationwide.

By mid‑century, the racing map looked both familiar and transformed. The old shrines — Saratoga, Pimlico, Churchill — remained the anchors. The flashy newcomers — Santa Anita, Del Mar, Keeneland — had firmly established themselves. Harness racing reinvented itself under the lights, and quarter horse racing began to scale up from dusty fairgrounds.

Most importantly, the industry had weathered its moral battles. The days of shadowy bookmakers ended. Regulated pari‑mutuel systems gave states something they could monitor and tax. Far from operating as an outlaw sport, racing had become respectable, even essential, to state coffers. America’s racetracks now stand as a testament to a century of shifting tastes, laws, and fortunes. Walk into Saratoga, Keeneland, or Santa Anita today, and you can still feel the echoes of those who built and rebuilt the sport.

Survival Through Transformation

In recent decades, a new economic reality has forced yet another transformation. Facing declining attendance, many tracks found a lifeline by adding casino gambling to their properties and becoming “racinos.” Venues like Prairie Meadows in Iowa and Dover Downs in Delaware use gaming revenue to subsidize racing purses and keep the sport alive. This evolution shows how the very ground of a racecourse continues to change in order to survive.

Ghost Ovals: History Written on the Ground

What’s remarkable, though, is how many of these old racetracks never completely disappear. Cities grow, suburbs sprawl, shopping malls rise, and industrial parks spread. Even so, from above you can still catch the faint outline of an oval that once thundered with hooves and cheers. The same holds true for countless county fairgrounds and shuttered courses across the Midwest and South. Their dirt rings slowly faded into farmland or subdivisions, but traces often remain.

These ghostly rings remind us that racing wasn’t just about the great names we remember. It was part of everyday American life. Tracks gave towns a gathering place, a site where people risked fortunes, and where entire communities looked for a spark of excitement. They also remind us that the landscape itself holds memory. Even when crews tear down the grandstands and the barns fall quiet, the geometry of the track endures, recorded from the air.

Racing as American Memory

These ghostly rings remind us that racing wasn’t just about the great names we remember. It was part of everyday American life. Tracks gave towns a gathering place, a site where people risked fortunes, and where entire communities looked for a spark of excitement. They also remind us that the landscape itself holds memory. Even when crews tear down the grandstands and the barns fall quiet, the geometry of the track endures, recorded from the air.

To study these aerial traces is to see history written on the ground. They are the signatures of an age when racing was king, when nearly every state boasted its own oval, and when the rhythms of hoofbeats and wagers left a permanent mark on the American landscape.

But the story isn’t over. For example, Pimlico Race Course survived for more than a century, yet a major redevelopment plan is now reshaping the site. A new grandstand will rise on the historic grounds, ensuring the Preakness Stakes stays in Baltimore while the surrounding land shifts toward community use. This project offers just the latest example of a racetrack changing shape to survive, a living testament to the sport’s resilience.

Ultimately, to study these aerial traces is to see history written on the ground. They are the signatures of an age when racing was king, when nearly every state boasted its own oval, and when the rhythms of hoofbeats and wagers left a permanent mark on the American landscape.