Say what you will about the demolition taking place at the White House to make room for a grand ballroom on its East Wing. The Trump White House ballroom project isn’t the first time the ‘President’s House’ has been torn apart in the name of improvement. It certainly won’t be the last. Every president seems to leave behind a physical mark—some more subtle than others—but few match the ambition of this one.

The Ballroom Project: Ambition and Controversy

The latest chapter in the White House’s long architectural saga is unfolding under Donald Trump’s direction. In July 2025, his administration announced plans for a 90,000-square-foot White House ballroom, rising from or replacing the existing East Wing. Private donors are reportedly funding the project, the cost of which is now estimated at $300 million.

Demolition of parts of the East Wing began this month. The administration temporarily relocated staff who once occupied the First Lady’s offices as construction crews peel back decades of history. The administration aims to create a ballroom that can host 650 to 900 guests. It would offer the kind of grand indoor entertaining space the White House has never truly had.

Reactions have been mixed. Preservationists have voiced concern that the project may have bypassed full compliance with federal preservation and review procedures. Among the critics: members of the Society of Architectural Historians’ Heritage Conservation Committee and the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Others have questioned whether the administration conducted proper environmental and structural assessments before demolition began Supporters, meanwhile, view the addition as an overdue modernization—a way to accommodate large events that currently rely on temporary outdoor spaces.

Details about the design and approval process remain murky. But one thing is clear: this is the most significant physical change to the White House complex in more than seventy years. Whether it enhances or detracts from the site’s historical integrity depends on how faithfully the final construction respects the original architecture.

A House Always in Flux

To understand the significance of this latest addition, it helps to remember that the White House has been a work in progress since the early 19th century. In fact, most president’s who’ve occupied the First Residence have remade it in varying degrees. Here’s a look back at some of the most notable transformations.

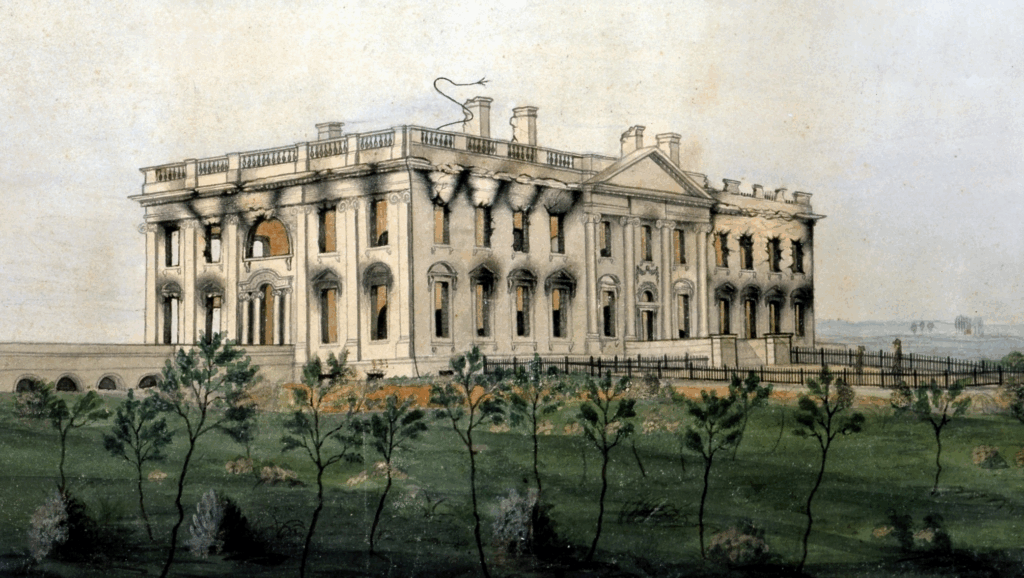

1814–1817: The Rebuild After the Fire

British troops set fire to the President’s House in August 1814 during the War of 1812. The blaze left a gutted, blackened ruin. Only the exterior sandstone walls remained intact.

Some suggested relocating the capital. President James Madison refused. He was determined to rebuild the iconic structure as a symbol of national resilience. The original architect, James Hoban, was brought back to oversee the reconstruction, which began in 1815. Hoban largely adhered to his original design but made subtle improvements. He incorporated more modern, fire-resistant materials. The restoration proceeded quickly. The exterior walls were painted a brilliant white to cover the smoke stains, solidifying its popular nickname: the White House. By 1817, President James Monroe was able to move into the rebuilt and refurnished executive mansion.

1829: Monroe’s Colonnaded South Portico

The two iconic porticoes that complete the White House’s Neoclassical facade were not part of the original 18th-century design. They weren’t included in the post-fire reconstruction either. But these were added more than a decade later. In each case, the original architect James Hoban was called back to expand on his earlier work.

The first of these additions was the South Portico, a graceful, semi-circular colonnade authorized by President James Monroe. Completed in 1824, it provided a stately entrance overlooking the South Lawn.

1829–1830: Jackson’s Portico

It was President Andrew Jackson who commissioned the addition of the North Portico on the Pennsylvania Avenue side—the grand entrance that defines the White House’s public face today. This new facade gave the mansion more balanced, formal symmetry, mirroring the South Portico. It helped elevate the building’s public presence. Its columned portico gave the building the formal neoclassical dignity it had previously lacked. It helped establish the White House as a symbol of executive authority recognizable to every generation that followed.

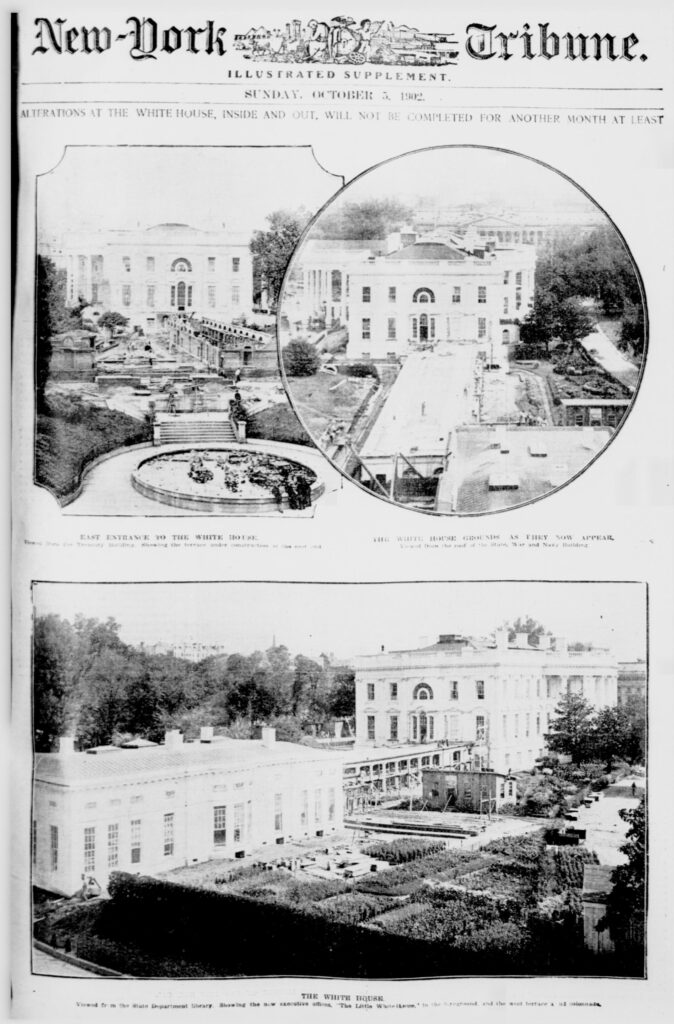

1902: Theodore Roosevelt’s Modernization

Teddy Roosevelt’s 1901 renovation was a pivotal moment. It was driven by the practical realities of the modern presidency and the domestic needs of his large family. Before this renovation, the second floor served as both the family’s living space and the president’s offices. The result was chaos: public officials, job-seekers, and staff mingling with the First Family’s daily life.

First Lady Edith Roosevelt was highly influential, insisting on a clear separation between the public and private spheres. The addition of the West Wing changed everything. All official business and thousands of ‘callers’ were diverted to a professional space. This finally secured the second floor as a private home for the president’s family and restored the State Floor to its intended role for formal public ceremony.

1909: Taft’s Oval Office

William Howard Taft’s 1909 expansion of the West Wing was a direct response to the functional limitations of Theodore Roosevelt’s original ‘temporary’ office building. Taft viewed the presidency as a hands-on administrative role. He found the existing rectangular office poorly located and insufficient for his operational style. The creation of a new executive office was a matter of practicality. It placed the president in the very center of the expanded West Wing. This new, more commanding position allowed for a more efficient flow of information and personnel, enabling Taft to be more involved in the day-to-day operations of his staff. The room’s famous oval shape was also a practical choice, intended to bestow a sense of history and formal authority on the new workspace.

1927: Coolidge Expands Upward

Calvin Coolidge’s 1927 renovation was a project born from urgent necessity rather than a desire for grandeur. After 128 years, the original timber-framed roof of the White House was failing, sagging, and declared structurally unsound by engineers. Instead of just replacing it, Coolidge authorized a major expansion. The entire roof was removed and rebuilt with a modern steel and concrete frame, pitched at a slightly steeper angle.

This clever engineering created a full, new “third floor” or “sky-parlor” within the roof’s structure, hidden from public view and preserving the building’s iconic exterior silhouette. This new space was purely utilitarian—it wasn’t glamorous, but it was essential. It added 18 new rooms, including proper guest suites, storage areas, recreational spaces , and, crucially, modern quarters for household staff, who had previously been housed in cramped, dark rooms in the basement.

1942: FDR’s East Wing

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1942 construction of the modern East Wing was a project driven by the urgent, dual necessities of a world war and a rapidly expanding federal government. The original 1902 East Terrace, which had primarily served as a formal entrance and cloakroom for large events, was entirely rebuilt into a much larger, two-story structure.

The public-facing purpose of this renovation was to provide desperately needed office space for the burgeoning White House staff and to create a more formal, permanent gallery for the public entrance to the mansion. However, the project’s most critical and secret purpose lay hidden beneath: the construction provided the perfect cover for building the Presidential Emergency Operations Center (PEOC), a hardened, bomb-proof bunker to ensure the presidency and military command could survive and function during a direct attack on Washington.

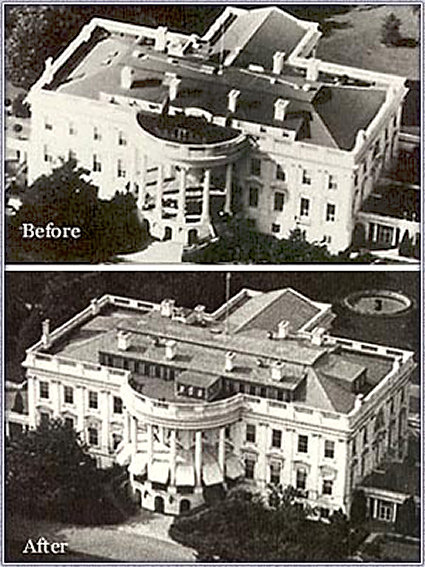

1948–1952: Truman’s Reinvention

During Harry S. Truman’s presidency, the White House was discovered to be in a state of near-total structural failure, famously punctuated by a piano leg crashing through the floor of the First Family’s private quarters. This precipitated a drastic and controversial gut renovation from 1948 to 1952, which saw the Trumans move to Blair House while the entire interior of the Executive Mansion was dismantled, leaving only the exterior walls standing. While this “great rebuilding” secured the building’s foundation, it was heavily criticized by historical preservationists for destroying much of the original, historic interior fabric in favor of a modern, steel-framed internal structure.

The most publicly debated element was the “Truman Balcony,” a new porch added to the second floor of the South Portico. Critics widely derided the balcony as an unsightly “back porch” that desecrated the building’s classic lines, but Truman fiercely defended it as a necessary private space for the First Family to enjoy the outdoors, and it has since become a beloved and integrated part of the White House.

1961: Kennedy’s Restoration

When Jacqueline Kennedy arrived with her husband’s administration in 1961, she found the White House furnished with department store reproductions, lacking any connection to its past. She immediately set out to transform the mansion from a mere residence into a “living museum” of American heritage. This was not just redecorating; it was a scholarly restoration. She established the White House Historical Association and a Fine Arts Committee of experts to acquire authentic, period-appropriate furniture and art, meticulously restoring rooms like the Green Room to the Federal style and the Blue Room to its French Empire origins. Her 1962 televised tour captivated 56 million Americans, allowing them to see “their” house’s renewed splendor. This single event redefined the White House’s image, cementing its status as a cherished national monument and a source of immense public pride.

1990s: Clinton’s Modernization

The 1990s brought a mix of polish and practicality to the White House. Under First Lady Hillary Clinton’s guidance, a privately funded restoration campaign set out to return several state rooms to their historical character. The showpiece was the Blue Room, painstakingly brought back to its 1817 James Monroe–era French Empire style. The State Dining Room, Lincoln Bedroom, and Lincoln Sitting Room followed suit, each gaining period-appropriate furnishings and textiles. Even the Oval Office got a fresh look—President Clinton swapped in a deep-blue rug emblazoned with the Presidential Seal.

Behind the scenes, the “White House 2000” project tackled the bones of the building. The aging HVAC system—last fully replaced in the 1950s—was overhauled, and crews cleaned and repaired the sandstone exterior. The Clinton years also nudged the Executive Mansion into the digital era: the first WhiteHouse.gov site went live in 1994, and email became part of daily operations. A few thoughtful touches rounded out the decade’s upgrades—a new East Wing ramp made public tours more accessible, and a quarter-mile jogging track curved its way across the South Lawn.

2009: Obama’s Garden and Grounds

When Michelle Obama arrived at the White House in 2009, she didn’t just move in—she planted a vision. Working with a group of schoolchildren, she broke ground on the White House Kitchen Garden on the South Lawn, reviving a long-dormant tradition of growing food at “the people’s house.” Over time the garden expanded (from about 1,100 sq ft to nearly 2,800 sq ft) and added a pollinator garden, beehives, recycled-wood furniture and wide walkways, all in support of her “Let’s Move!” initiative for healthier nutrition.

2025–: Trump’s Ballroom

Trump’s addition joins the long continuum of presidential renovations—each one controversial in its own time. Like Truman’s steel-frame rebuild or Roosevelt’s creation of the West Wing, this ballroom represents more than a construction project; it’s a reflection of how each administration reshapes the presidency’s physical and symbolic space. The East Wing’s demolition recalls the cyclical nature of change at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue—where innovation and preservation often collide.

Preservation, Procedure, and Perspective

Critics argue the project has moved too quickly, bypassing traditional review processes meant to safeguard national landmarks. Others see it as the next logical step in adapting the Executive Mansion for modern use—a facility that must balance ceremony, security, and statecraft. History suggests both sides may be right. Nearly every major alteration, from Jackson’s portico to Kennedy’s restoration, faced public skepticism before becoming part of the White House’s accepted story.

Acknowledging the concerns raised by historians and preservationists is essential. The White House is not just an active residence—it is one of the nation’s most significant architectural symbols. Federal law typically requires that major changes to landmark federal properties undergo rigorous review, balancing functionality with historical integrity. If Trump’s ballroom project bypassed or abbreviated those reviews, that sets a precedent worth discussing.

Still, history shows that controversy often accompanies transformation. The Truman reconstruction faced fierce criticism before being widely praised for saving the structure. The same could prove true here… or not. Renovation and preservation have always been uneasy partners, and the White House has stood at the crossroads of both for more than two centuries.

Whatever judgment time delivers, the ballroom will embody this era’s priorities: scale, spectacle, and the desire to leave a lasting mark. Once complete, it will add a new shape to that familiar outline. Future aerials will capture it the same way earlier generations documented Roosevelt’s new wings or Truman’s rebuilt core—a reminder that history is never static, even at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.